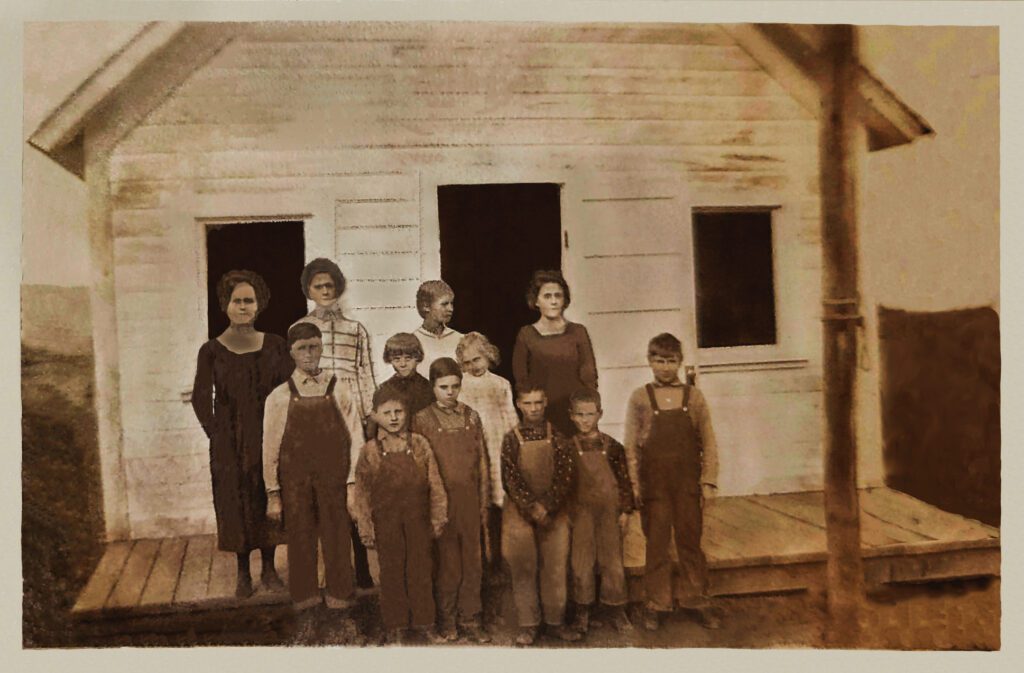

Albert sat at the end of the long bench in the little white schoolhouse, nearest the window that looked out toward where Strawberry Creek1 flowed down from the flanks of Strawberry Mountain. Part of him wished he was seated nearer the pot-bellied stove, but they always let the littler kids have those seats. The other part of him wished he was out on his horse, maybe following the creek draw up higher and looking for deer. Ma would appreciate some fresh venison.

The weather had turned cold, and bone-chilling winds blew up the John Day Valley from the west. The hay had already been brought in for the winter, and outside of helping with harvesting the last apples from Rinehart’s orchard, there wasn’t much work left to do outside. Soon the long winter would set in and there’d be little else but winter hunting, feeding stock, and keeping warm.

Albert gazed out the window, longing to be outside. Up where the tree line met the fields, he saw a rider coming hard. The horse’s neck outstretched, the rider’s whip hand coming down on its flanks. He watched as the rider headed into the valley, saw the sun glisten for a moment off the big red horse, saw the white blaze and knew in an instant it was Charley2, coming in from patrolling the southern slopes of their valley.

He glanced at the teacher, gestured quickly to catch her eye, then nodded towards the foothills and mouthed, “Rider.” She glanced to the window, clapped her hands, and in a firm voice said, “Children, get your coats.” Without a fuss the children grabbed their coats, headed outside and around back where the older children had horses tied. Albert got Ms. Day’s horse saddled while she hoisted the smaller children onto the horses of the older children. Charley was still aways off, but he could see the bustle of children and horses at the school and knew they were aware, so he turned west towards Canyon City and urged his horse forward to continue his warning of the band of warriors he’d seen coming over from Summit Prairie. Just to the south of the school was Camp Logan. The watch had seen Charley’s signal as he came down the hills and had sounded the alarm. Soldiers prepared arms and horses, and the watch looked north towards a plume of dust as the children made their way to the camp.

On May 8, 1866, Sheriff M. P. Berry wrote to Gov. A. C. Gibbs, “The property of a large portion of the citizens of this country is being continuously carried off by hostile Indians. One murder had been committed within ten miles of this the County Seat, and several citizens have been wounded. A perfect horror exists throughout the larger portion of my baliwick, no one is safe to leave his family for an instant alone; the farmers have had to cease planting for reason that it is unsafe to go into the fields, and the last reason that the work stock in nearly all driven off.” 3

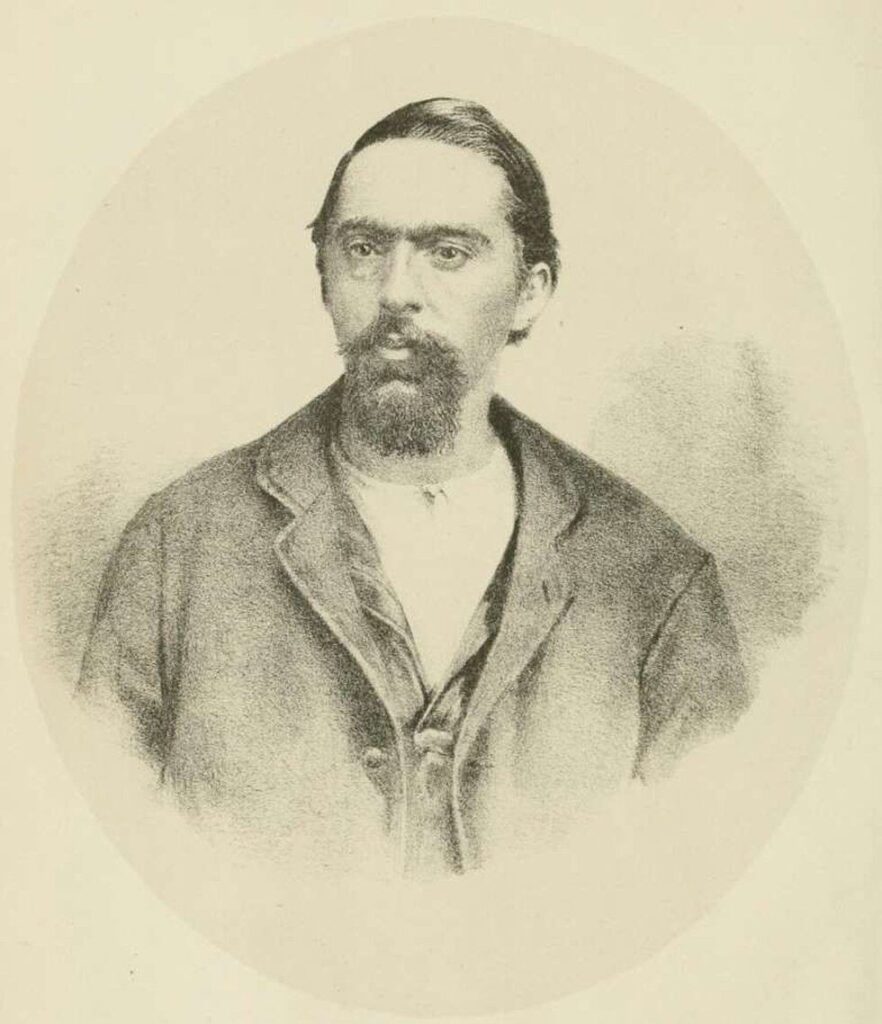

William “Ralph” Fisk (1852-1933) often wrote stories to the editor of the Blue Mountain Eagle. In one he states, “The reader wants to remember in those days that Indians with their war paint, bows and arrows and guns were on the alert everywhere in the surrounding country, liable to spring up anywhere and anytime when least expected, as they were stealing and killing all the time.”4

Camp Logan was just one of several camps established to protect the Dallas to Boise Road, as well as the settlers (see map link above). Summer to fall of 1867 saw 106 horses, 99 mules and more than 30 cattle taken by bands of warriors. More than a half dozen people were wounded in skirmishes, and two were killed.5 In the minds of most residents, it was indeed “a perfect horror” as Sheriff Barry had described.

Second Lieutenant James Pike turned his gaze south to see the rise of dust from the children racing towards the camp. He’d had enough. With a half dozen men and two civilian guides, he took the trail north into the Blue Mountains in pursuit of the band that Charley had spotted.

Late in the day they found a band of about thirty Indians encamped in a canyon near Reynolds Creek. They silently made their own camp above the canyon, and the following morning, with the element of surprise, Lieutenant Pike ordered a charge.

Described by Sergeant Bruce as “a man who had no fear and too little caution,” Pike was the first to swoop in and seize a rifle from the hands of a warrior. Striking the breech of the gun to the ground, it discharged into his right thigh. As attention turned to their fallen Lieutenant, the Indians escaped, and the soldiers carried Lieut. Pike to the ranch of Mr. Douglas, while a rider sped to Camp Logan for medical aid.6

On October 15 at 4:35 pm, Lieutenant Pike died, and he was interred on a rise east of camp overlooking the valley and Strawberry Creek. Ralph Fisk recalled that his “mother furnished the necktie and put it on him the day of the funeral in remembrance of the bravery and good of Lieutenant Pike.”7

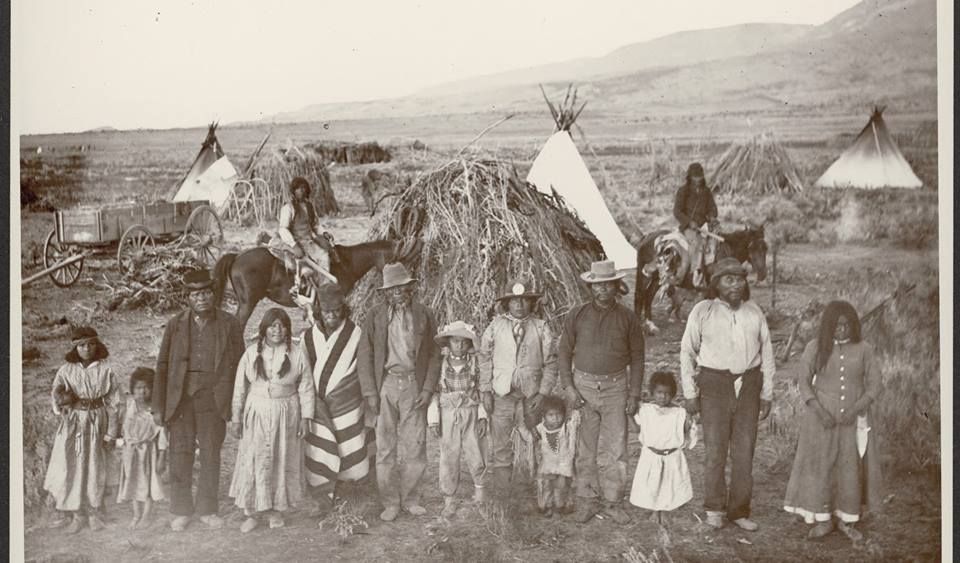

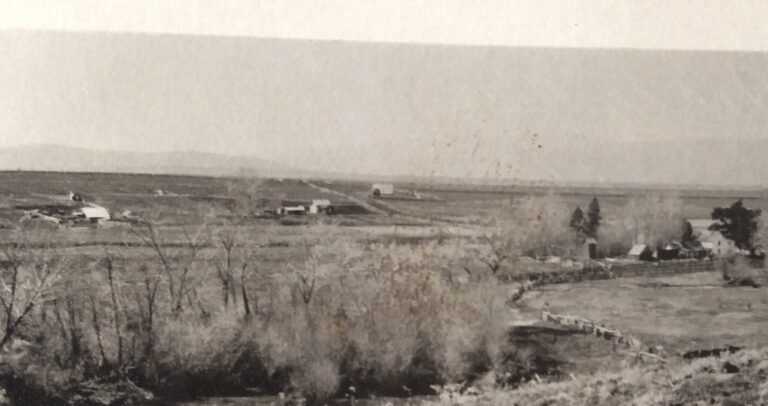

The conflicts continued, until such time the Paiutes were subdued, primarily at the hand of General Crook. By 1870 Camp Logan was abandoned and the Kent family eventually took over ranching at that site. The Snake War, the battle with the northern Paiutes, came to an end with their forced surrender, and while the fear may have subsided for the settlers of that land, a great sadness also came.

As one Chief reflected upon surrender, “Your great white people are like the grass; the more you cut it down the more it grows and the more numerous the blades. We kill your white soldiers and ten more come for every one that is killed; but when you kill one of our warriors, or one of our people, no more come to replace them. We are very weak and cannot recover.”8

The fear the children must have felt that day as they rushed to the safety of Camp Logan has, over time, been replaced by a sadness that tinges our history. While I cannot speak to the sadness of the Native Americans who lost their homeland and their way of life, I can speak to my own. It is a sadness I think I have felt all my life, since the time as a small boy living in the former lands of the Nimíipuu, and reading about their way of life and their fight against the Manifest Destiny that swept them from their lands in the wake of the great migration along the Oregon Trail.

My own family felt the fear of Native American reprisals. I know that they hunted them, and that they killed them. There were also family members who had compassion for and befriended Native Americans, forming friendships and relationships that are as much a part of my history, our history, as is the history of subduction of another culture. I understand how it came to be, how moral and political forces shaped our actions, and those actions built this country, while simultaneously sweeping another way of life aside.

While we rejoice in the accomplishments of our ancestors, marvel at their courage and perseverance in settling these lands, while we build our family trees, and reconstruct our histories, I think it must not be forgotten the price of those efforts. History has always been the great teacher, and the price of sadness is part of that history, reminding me of who I want to be, and what I want to teach my children.

1 – In 1865 Strawberry Creek, as it is known, was sometimes referred to as Indian Creek, and it was along Indian Creek (Strawberry Creek, about six miles south of Prairie City where the Kent Ranch was later located, that Capt. A. B. Ingram first established Camp Logan. McArthur, Lewis A., Oregon Geographic Names, 2nd Edition. Portland, Oregon: Binfords & Mort, 1944

2 – According to Thomas Cooley’s Memoirs, published in the Blue Mt. Eagle, 1975, his father, Charles Cooley, was riding pony express and was an Indian scout in the Valley, warning folks to get to the fort when Indians were spotted.

3 – Sheriff Barry, Letter to Gov. A. C. Gibbs, Portland, Oregon, May 8, 1866

4 – Memoirs of William “Ralph” Fisk, in this authors collection. His parents were Nathan & Esther Fisk, who traveled the Oregon Trail in 1852, my ggggrandparents.

5 – United States, Report of Indian Affairs 1867

6 – The Dallas Mountaineer, October 12, 1867; United States War Department: Annual Reports of the War Department, US Govt. Printing Office, 1868, pg. 771.

7 – IBID, Memoirs of William “Ralph” Fisk.

8 – Peter Cozzens, Eyewitness to the Indian Wars 1865-1890, vol. 2 The Wars for the Pacific Northwest (Stackpole Books, 2002), 31.

Rosemary

Regrettably, we as a nation need to overrun those in our “way”. And it is still happening worldwide.

Thank you for a fascinating article.

Mgoddard

Thank you Rosemary, I’m so pleased you enjoyed it!