An account written by Arlene Blevans Reams of her life in Oregon (unedited)

In a previous story of mine, “Two Families, One Ancestor, Two Hundred Miles Apart“, I included a quote from a little girl in the Imnaha, with an intent to show the happiness of life in those times, in what was nothing less than wilderness.

While the story centered around the Shields families of the Imnaha and Long Creek, it also triggered connections I could not have imagined. As I write these histories, I am continually amazed at the connections, both to my own family lineage, and to others whose families had a role in the settling of the Oregon Territory.

So it was, that a descendant of the little girl I’d quoted at random, contacted me and kindly shared her family’s remarkable story of traveling the Oregon Trail and settling in the gorgeous valley of the Imnaha. Stories came from Arlene’s mother Jennie, and then gathered by Arlene into her own stories. And with marriage, the Blevans were entwined with Beith’s, and yet another account surfaced, “Crossing the Plains” by W.G. Beith.

Oregon Trails Genealogy started as a means to share the stories and history of my family, and to help others find their family stories. I cannot be happier to see my website unfold and become a place where these remarkable stories can be shared. It is rare to find a family with such depth and documentation, and so, since it was Arlene that I first quoted, it seems only right that I have her tell her own story:

Grandma Remembers

A story dedicated to my very dear grandchildren, with the wish that they might see these things as I saw them. This story is true. So to my grandchildren, Roxy, Sally, Laine, Bobby, Shirley and Karen Reams, and any others who wish to join us later, I write of these things which happened many years ago. It was almost seventy years ago when the story starts. So…Come gather around my knee and listen while I tell you the story of a Boy and Girl who lived away up on the Imnaha River in a log cabin.

Their Papa and Mama (Children did not call their parents Daddy and Mommy in those days.) homesteaded one hundred sixty acres of land.

To homestead land you must first file your claim on it, then build a house and other buildings, and a certain amount of fences. You must make it your home for four years. Then it is yours, after you have “proved up” on it. It was virgin land which means that it had never been owned by anyone but the Indians and the United States Government. In the meantime you are called homesteaders.

So Papa and Mama and the Boy who was one and a half years old, had given up their claim on the Divide. (The Girl was not yet born.) Their four year old boy had died of diphtheria, a dreadful disease, and they felt so bad that they wanted to move away. The winters were harsh there. The wind blew all the time and drifted snow around the house until they had to dig a way out from the door. The windows were drifted under.

So in the fall of 1893 they packed their belongings in a spring wagon, hitched up their team and left for their new home.

It took them three days to get there as the roads were terrible. From the Divide they drove down a road which wasn’t much better than a trail which led them to Bear Gulch and from there to Little Sheep Creek. They bounded along in the rough riding wagon fording the stream many times as there was no road then as there is now.

Mama got very tired holding the Boy who got tired and cross and wished he was back on the Divide.

They got so weary that they camped overnight. They cooked their supper over a campfire then went to bed on the ground where Papa had put some comforts on some straw. The Boy wasn’t use to sleeping out doors or on the ground and didn’t like it. Mama was tired and the night seemed long. It was getting cold now as winter wasn’t far away so Papa build a big camp fire in the morning and they ate breakfast and were again on the road. Papa and Mama began to wonder if it wasn’t a foolish thing to move so far away from their friends.

But the day was beautiful, the sky was a bright blue. The leaves on the quaking aspen and the cottonwood trees were a bright yellow , and the sumac was bright red with its autumn dress. The woodbine was at its handsomest, climbing everywhere. The blue jays with their brilliant blue plumage scolded them for coming near their domain. The kingfisher squawked his little song as he sat on a limb looking for fish in the water below him.

Very soon, that second day, they reached the Bridge and crossed over and began the long slow journey up the river. Their new home was twenty-two miles up the river. They would find no more bridges but must ford the river over twenty times.

The roads were very bad. Just barely wide enough for a wagon to travel on. They were rough, rocky and steep. The fords were rocky and Mama had to hold fast to the Boy to keep him from bouncing out as Papa drove the horses over the rocky river bed. It seemed that they had hardly got over one bad jolting until they had to ford again.

The mountains on either side of the river were high, steep and majestic in their tawny autumn coat. The rim rocks were fantastically shaped, looking like old castle ruins. They saw many brush pheasants and once saw several deer across the river. One huge Buck with wide- spreading antlers.

The cabins along the river looked comfortable and homey. The river was most beautiful and they thought that surely this was a fine country.

When they reached the part of the River which is called Freezeout they saw a cabin below the road. It was visible some distance down the road. When they came to the gate a man whom they use to know came out with his wife and asked them to stay all night. O, how good it was to see old friends! They lost no time in letting them know that they

would gladly accept their invitation. These good friends were Sam and Mary Adams. They had two big girls. They spent the rest of the day visiting and Mrs. Adams made some huckleberry pies to celebrate the occasion. How good it was to sleep in a bed after sleeping on the hard ground. Mama was tired so she slept well. It was a good thing as they had another hard day ahead of them, fording the river, and going over the famous old Saddle grade, that by-passes the Saddle Gorge.

It began climbing the hill at the upper end of the Freezeout area. It was just a narrow road gouged out of the hillside and it kept climbing and climbing until you could see the river far, far below. Mama was afraid when she looked away down the hill and held on tight to the Boy. They had to rest the horses many times before they reached the Saddle, then they crossed over and dropped down the other side to the portion of the river that is still known as The Park. They had only five miles to go now but it took quite a while. But that afternoon they forded the river the last time and came to the cabin where they would spend the winter.

It was a small, mean cabin, isolated and forlorn, standing on a flat surrounded by trees. There was a dirt floor. In other words no floor. Only one small window. There was a small fireplace in one end where Papa soon had a fire roaring. He found some wood that the trapper who owned it had left. There was a ramshackle bed in one corner and some shelves on the wall and that was all.

They lived here the first winter. They had a coal oil lamp. We now call it kerosene but in these days every one called it coal oil. And a coal oil lantern. That first winter they used candles mostly because they didn’t have much coal oil.

I do not think they had much to eat that winter. Papa killed a deer now and then. There were no game laws then and any one could kill any sort of game any time they wanted to. But they had enough to keep from starving. It was a long dreary winter but the neighbors were good and they visited quite a lot. In the Spring a neighbor down the river less than a mile asked them to move into a cabin that was on their place. It was a much nicer cabin and quite close to these people’s cabin. Their names were Byron and Annie Janes. They had a boy Glen and a girl Nora.

Mama taught school in the little log school house down the river two miles for three months that Spring. Mrs. Janes took care of the boy. Mama got $25 a month.

Papa was busy all summer cutting down trees for logs for their new cabin. He hauled them to a place on the other side of the river from the old cabin, where the new one was to be built. They built it back from the river so the Boy and the new child they were to have the next fall wouldn’t fall in and drown. Papa peeled the logs and made shakes to cover the roof.

The leaves were again turning a brilliant yellow when they had the house raising and it was in November before it was ready to move into. Papa had had to make a trip to town to get lumber for the floor and door and window frames. He had to buy nails and a pair of hinges for the door and a thumb latch. But at last it was finished, the cracks chinked and mortared with mud, to keep out the cold.

The cabin was one room, about twelve by twenty-five feet. You wouldn’t think much of it as a place to live, but after being crowded into a small cabin that belonged to some one else it seemed mighty fine to Papa and Mama and they were very proud of it. They papered the walls with newspapers and people who came to see them use to stand and read the papers on the wall and be frustrated when they couldn’t find the finish of something they were reading. There was one window in each end. Each window had but one sash so it wasn’t very light, especially when the days were short.

There were two stoves in the cabin. One heater right in the middle of the room and the cast iron cook stove with four lids, and a hearth in the front. It stood on legs. There was a damper in front and it had a small oven. The firebox door let down and we toasted bread by using an iron fork to prop the slices up before the blaze. We burned them lots of times.

Papa made two beds out of some of the lumber he brought from Joseph. One double bed for Mama and Papa and a narrow bed for the boy. After the Girl was born and got too big to sleep with Mama and Papa, he made a trundle bed for her and it slid under the Boy’s bed in the daytime.

There was a dining table and a big cupboard, the same old red cupboard that Grandma has in the “dark room” to this day, that were made by Mama’s father, Grandfather Beith for Grandma Beith. The only furniture that wasn’t home made were the four “boughten” chairs that we used at the table. There was a home made willow rocker, a wash bench and a table to cook on. Also a big flour bin that held about

three large sacks of flour.

A mirror that was Grandma Beith’s hung over the wash bench. It had a nice frame but the glass was yellowish and it didn’t make you look very pretty.

On the cook stove was a cast iron tea kettle, real heavy to lift. There was also a huge kettle, pancake griddle and muffin tins of the same material. The coffee pot and tea pot were of blue and white enamel ware. The table tops were covered with dark colored oil cloth. The dishes were mostly heavy white iron stone china made to last a long time. The cups were made without handles. The heavy ones that we used were at least.

There was a real nice set of glass ware including a spoon holder, cream pitcher and sugar bowl. The knives and forks were steel with black wooden handles inlaid with a while metal of some sort. The spoons were of a metal called German silver. If you left them in food long they tarnished badly.

When the Girl grew older it was her chore to keep the knives and forks and spoons scoured. They had no cleansing powder like we have today. Our cleansing powder was “chalk” from a chalk bank about five miles down the river. It must have had alkali in it instead of chalk as it is a very effective cleanser.

They hung every thing on the wall that could be hung there as they had no chest of drawers. Only two trunks and of course they couldn’t hold everything. They hung every frying pan, griddle, bread pan, and dishpan on nails behind the stove. All clothing was hung on nails, Papa’s guns and his beloved fiddle too.

Mama had an old Wheeler and Wilson sewing machine that she had earned money for by teaching school before she was married. She was very proud of it for not nearly every one had a sewing machine in these days.

On the wall was a clock shelf upon which sat a most beautiful Seth Thomas clock that Grandpa Blevans had brought back from Missouri. They were all very proud of it as they had so few nice things. It had an alarm too and it made a fearful sound. It scared the Girl half out of her wits when it rang.

On the shelf above the work table were bags of pepper corns, unground allspice, ungrated nutmeg and cinnamon sticks. They ground the pepper corns, which were round black seeds about the size of a pea,

in the coffee mill. Also the allspice which looked like the peppercorns only was brown. The cinnamon sticks, which was bark from the cinnamon trees, was used in pickles. The children liked to chew it.

Nutmegs had to be grated on a nutmeg grater. We could get some spices in cans like we do now but almost every one ground their own.

Tea was called Gunpowder tea, or at least they used that kind. It was cured in small round pellets that were about the size of shot from a shotgun.

They bought coffee beans that were green and had to be roasted, then ground in the coffee grinder.

O yes, they had another bit of furniture. A footstool that was made by covering a real strong wooden box about fifteen inches and 7 inches high with pieces of black velvet, set together with turkey-red feather-stitching. It served them long and well.

This one room was a bedroom, kitchen, living room, dining room, laundry and bathroom, all in one. They took their Saturday night baths in a wooden tub in front of the cook stove, in water that had been carried quite a long ways from the river and heated in a small copper boiler on the little iron cook stove.

The washing was done in the same tub on a bench, with the use of a wash board and it was wrung out by hand. The white clothes were boiled in the small boiler and poked down with a “clothes stick”, which was usually a length cut from an old worn out broom handle. They couldn’t wash with out this clothes stick as it was the only means by which clothes could be gotten out of the boiling water to be sudsed in the same old tub in fresh water and later rinsed by the same means.

Bluing was always used in the rinse water to make the clothes white. The soap was home made lye soap. Any way they (the clothes) were much whiter and cleaner looking than the clothes are now that are washed in the automatic machines. They were hung out in the sun for at least a day and a night. In the winter they must be dried indoors.

Later they had hand operated washing machines and wringers run by hand.

They had pretty quilted quilts on the beds and braided or

crocheted rugs on the floor. Turkey Red window curtains hung at the windows. They were pushed back in the day time to let in every bit of light that there was.

So my dears, this is a pioneer cabin. There were many much

nicer than this one. Some had a kitchen built on to the cabin and some had an upstairs. And some were much smaller than this one.

I must tell you about the beds. They had no springs and no mattresses but they had ticks, they called them, filled with hay or straw. These ticks were made of flour sacks sewed together. They were about the size of the bed. A comfort was put over them. Some people had these ticks filled with feathers. They called them feather beds. Both kinds were lumpy and not very good to sleep on.

The cabin had pine trees in the back yard that gave shade in the summer time. Birds built their nests in them and squirrels sometimes ran up and down them. And once, a long time after, when the Boy was almost grown up he caught some cub bears. They had them for pets and they ran up and down these trees.

That same winter that they finished and moved into the cabin the girl was born. They had looked for her in the middle of November but here it was December sixth and she hadn’t come, so Papa decided he’d go out and kill a deer. He thought I suppose if she had waited that long that she could wait another day. Aunt Clara, Mama’s sister was there. She lived on the Divide and she was afraid she’s get snowed in so she was very anxious to get it over and get home. So Papa went hunting.

Mama told Aunt Clara quite soon after Papa left that she felt sure the baby would soon be here. It was very cold and the footlog between the house and the Himelwrights just across the river was icy and had no railing. Aunt Clara wanted help. She didn’t want to be alone with Mama so she didn’t know what to do. Whether to try to cross the log and maybe fall in and kill herself and then there would be no one to help Mama, or whether she’d better stay with Mama. She finally decided to go try the foot log. She got across all right and Mrs.

Himelwright and her two little boys came right over. Now Mrs. Himelwright didn’t know any more about helping babies to be born than Aunt Clara did so they sent Mrs. Himelwright on a horse down the river three miles to get Mrs. Rich who was much older and who was experienced with babies. So when Papa got back in the afternoon he found a lot of excitement. He flew around trying to do every thing at once to make up for being gone when they needed him. So the Girl was born at 8 o’clock that evening. She wasn’t quite all right as she strangled and couldn’t breathe. Mama and Aunt Clara and Mrs.

Himelwright were scared silly but Mrs. Rich ran her old bony finger

down the baby’s throat and got out a lot of phlegm and she started breathing all right so every one was happy. Papa made some coffee so strong that the good ladies couldn’t sleep all night. The littlest Himelwright boy pulled a table cover off a table bringing the lamp with it. They were afraid it would burn the new cabin up. The Boy ran over and picked up the lamp chimney and burned his hands very badly. He was only two and a half years old but he remembers it. The boy who pulled the cover off the table is now the County Judge of Wallowa Co.

After Aunt Clara went home Papa decided he’s do the washing.

Mama wanted to tell him how but Papa wasn’t a man who would let his lady folks tell him how to do things. Before the baby was born Mama had made the Boy several nice dresses out of light colored percale. Boys wore dresses in those days until they were three years old. These dresses were all in the wash. Papa gathered them up with an old pair of overalls of his, some dirty sox and dark shirts, and every thing he could find. He put them all together in the boiler on the stove and poured water over them and whittled a bar of lye soap over them, put on the boiler lid and let them boil. He took the clothes stick now and then and pounded them down. After they had boiled a long time he rinsed them through a water or two then wrung them out and hung them out to dry. Poor Mama never all her life got over grieving for those lovely dresses. She tried every way to get them white again but she never could.

The winter was long and snow fell deep, but they were snug and warm in the cabin and spring came at last. Spring on Imnaha is a lovely thing. The skies are nowhere bluer. The grass is nowhere greener. The birds sing nowhere sweeter. There are many wild flowers. Many little wild animals skittering around in the woods. Mama loved all these things. She set out lilac bushes. All the neighbors gave her “starts” of plants of all sorts. Sweet William, Clove pinks, flags, white anemone known as iris, forget-me-nots, and pie plant, you call it rhubarb now, horse radish and sage which they used to season sausage, gooseberry bushes, currant bushes and raspberry bushes and strawberry plants, They set out cherry trees and apple trees. They built a cellar to keep food cool.

Papa built fences, cleared the land so he could raise hay for the cows and horses.

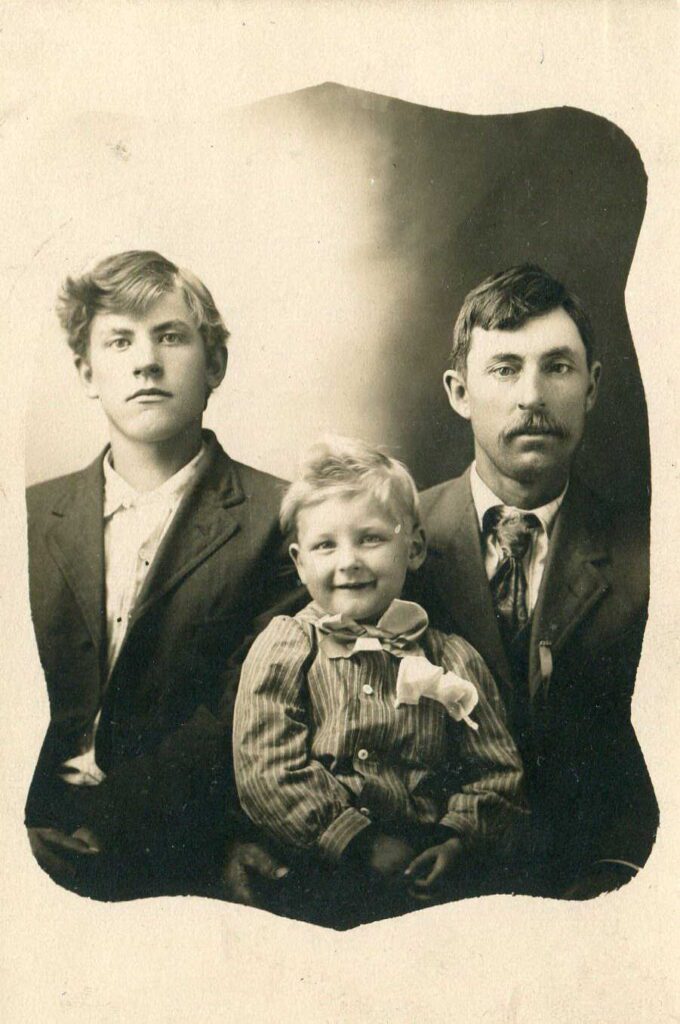

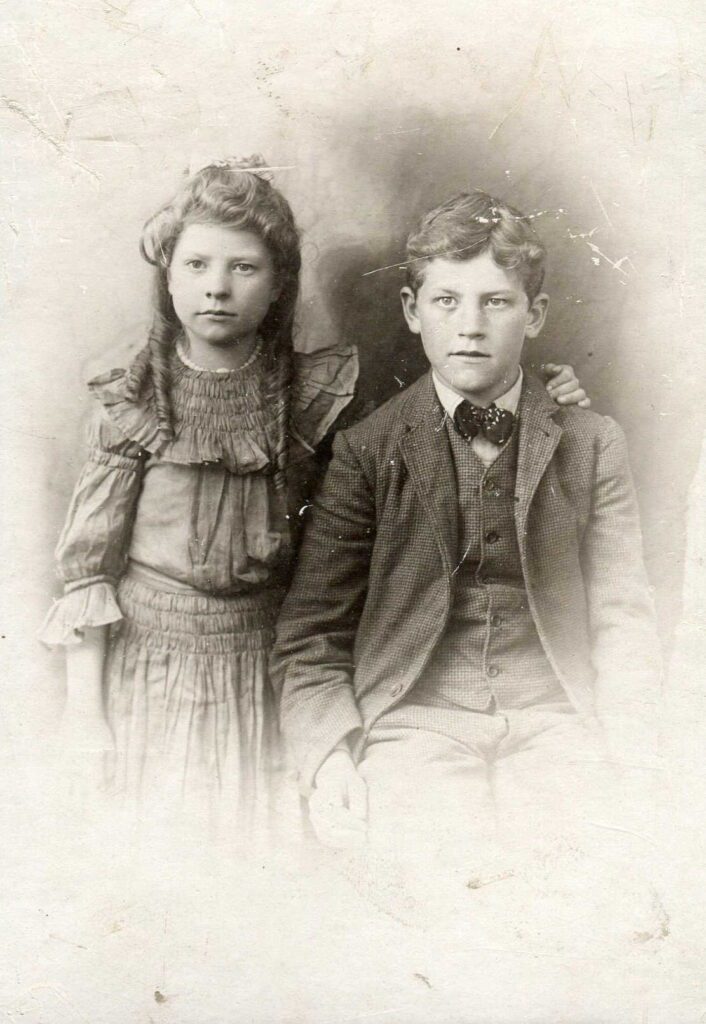

The years rolled by. The Boy and Girl grew.

Each summer Papa went “across the mountains” to work in

harvest fields to earn money to buy food and clothing. It seemed to us that he was gone a long time and we were very lonely with out him.

When it came time for him to come home we’d listen for the sound of a wagon. When anyone passed the Himelwright place their dogs always barked. Every time we heard these dogs bark we’d wait and see if a wagon was coming. If we could hear a wagon we’d be all agog until it came in sight. Many times we were disappointed but finally one day here he came. What a happy day that was. It didn’t seem right with Papa gone. He always brought the children something.

By this time Papa had built a “milk house” of large hewed logs to keep milk and food cool in the summer time. They planted hop vines all around the milk house and they completely covered it and they helped keep it cool. Mama had a screened cupboard where she kept the milk in milk pans, which were large round pans not very deep, so the cream would raise well. She had a cream skimmer that had holes in the bottom that she lifted the cream with. When she had enough we would churn it with a paddle like this + on a stick. There was a lid to the churn and it had a hole in the middle where the handle came up through. You kept this paddle going up and down till butter came.

Mama worked the butter milk out of the butter with a butter paddle, salted it and molded it in butter moulds. You never tasted such good butter and on Mama’s wonderful light bread. It was as good eating as a boy or girl could want.

Papa built a barn to hold the hay. It was made of logs too and had a shake roof. There was a shed built on one side for the horses and cows. It was fun to go visit the horses and pet them and feed them carrots.

The hay mow was fun too when it was full of fragrant hay. The children turned somersaults and dropped from the topmost heap of hay to the lowest pile they could find. Or slid down the slippery sides. You would have loved it. And you would have loved to take a book and some nice ripe yellow transparent apples and curl up in the hay and read. It was a safe place to get away from work when Mama wanted us to go across the river and weed the garden. Some times the pet cat would come curl up by you and purr himself to sleep.

On rainy days it was fun to go there and listen to the rain. The boy took his bed there summers and the song of the river put him to sleep at night.

There was a chicken house not far from the barn with roosts on one side and a row of nests of the other where the hens laid their eggs. The girl used to love to take a lard bucket and gather the eggs in the evening. She fed the chickens too.

Early in the spring the hens had the urge to raise a family so they would start clucking around. Then they would get on a nest and stay there and squawk if any one came near them. So Mama would take about fifteen nice big eggs and mark them with a pencil so if a hen laid another egg in the nest after she started setting, that they could tell which one to take out.

It takes three weeks for eggs to hatch. So after Mama put the eggs under the hen she would write down on the calendar what day they would hatch. The children could hardly wait. Mama watched very closely and as soon as the first chick hatched she cuddled it in her hands and took it to the house and put it in a box in a warm spot. She put a piece of warm blanket under and over it. Soon they would all be hatched. How the children loved these little fluffy babies. Mama could hardly keep them away from them.

Then Mama would take the hen out of the nest and put her under a coop. She would put feed in with her and a pan of water. Then she would give her her babies. How she would cluck! cluck! cluck! until she had them all under her wings. She kept her there two or three days then she turned her out. With a cluckety, cluck, she called the chicks to follow her. It was so good for the hen to be out under the bright blue sky again with the warm sun shine warming her and a fine new family to raise. She would stop and scratch every little while, thinking maybe she’s find some nice gravel. She hadn’t had any gravel for three weeks. Or maybe she’d find a nice fat worm. Her babies scratched too with their little yellow feet, and ran flapping their baby wings.

There were baby ducks sometimes too. The cutest little things that you could ever imagine. There was a little pond that the children had dug to play in. Mama duck use to take her babies there for a swim and they would have a grand time.

But Mama quit raising ducks because they would find their way to the river when they were nearly grown, and away they would go paddle footing off down the river and would never be found again.

Some times the neighbors would see them going by but they couldn’t catch them. We never did know just what became of them.

Mama tried raising turkeys too and sometimes she sold quite a few along about Thanksgiving time. The little turkeys were cute too but they were forever dying and it was such a difficult job to care for them, that Mama gave it up. But we missed the turkey gobblers gobblety gobbling around the place with their beautiful tails spread out like a fan. They gobbled when any one came by them or when the dog went near them. And they gobbled just to hear their voices.

They use to have guinea hens too. Did you ever see a guinea hen?

I couldn’t describe them so you would know what they looked like. They would go a way up on the hill and sail back down to the barn lot. They were wild and made a fearful racket with their constant Pat-rack! Pat rack! Pat rack! When they wanted to raise a family in the spring they would hide their nest out a long ways from the house. If anyone found the nest and handled any of the eggs, they would leave it and find a new hiding place. When their babies were hatched they would bring them back to the barn yard. People thought that the racket they made kept the hawks away. The hawks use to catch chickens and kill them and eat them so all the family would shoot every hawk they could see.

The guinea hens were very beautiful but one sees them very rarely now.

Every spring the children would get “bummer” lambs. Lambs that had no mother, or maybe their mother wouldn’t claim them.

Sometimes they were one of a pair of twins whose mother didn’t have enough milk for them. The children’s Uncle Walt had a band of sheep and every morning during lambing season the children would get on their ponies and ride down to his ranch and get any lamb that he had to give away. They fed them out of bottles, or sometimes taught them to drink out of a pan. The lambs thought the children were their mothers and followed them every where they went. They played “follow the leader”, and frisked around and jumped up on rocks and off of them and were very nice pets. Sometimes they sold them back to Uncle Walt in the fall. Or kept them and Papa would shear the wool off of them and Mama would make warm comforts and fill them with this wool, to keep them all warm in the long cold winter nights. If there was any wool left they would sell it.

The calves were a lot of fun too, frisking around the barn lot with their tails up and bucking and butting each other.

But what you would most dearly love were the colts! How the

Girl adored them with their soft velvet noses and their winsome ways. Whenever there was a new colt Mama had an awful time getting the Girl to stay in the house long enough to do her work. The colts bucked and played too and tore up and down the field at break neck speed. I am very much afraid that the Girl spoiled them as they were hard to break into good riding horses, and always had a lot of bad habits.

A bachelor, John Owens who was also an Irishman, lived in the Quirk cabin about a mile above the homestead. He trapped in the winter. He had quite a few horses. He was a lonely man and came to see Mama and Papa often. He liked the Girl quite well. She was about three years old at that time. He held her on his lap and she “read” to him out of what she called her “tuss cady,” which was what she called her first reader. She made Mama read the stories to her so many times and she heard her brother read them too, so she soon learned them all by heart. So when she “read” she just recited them from memory. Mr. Owens thought she was awfully smart and told the neighbors how she could read and her only three years old. She did learn to read not long after that.

Papa cut Mr. Owen’s hair and Mama fed him good home cooked meals and washed his clothes up for him some times.

He wanted to pay these good people some way so he rode up one day leading a most beautiful young mare. She was a dark buckskin mare with a flowing black mane and tail. She had the nicest head and looked a good deal like the pictures of those beautiful Arabian horses that you have seen.

Mama took her for her riding horse. Uncle Bill had given her a gray mare she called Selma. But Selma was built for a work horse and Papa teamed her up with another gray mare he had whose name was Net. Papa always rode Net.

In these days they rode horseback nearly every where they went. Papa on Net with the Boy on behind, and Mama riding a sidesaddle on the buckskin mare, with the Girl behind her, with her short fat legs sticking almost straight out.

They named the new mare Fanny. When the Girl grew older she learned to ride alone and as Fanny was so good, and so gentle she learned to ride on her. When the Girl got old enough to put the bridle on Fanny, she would drop her head down so the Girl could reach it and put it on. And she would sidle up to a fence so the Girl could climb up

on the fence and get on her back. When they went down a steep hill, and you couldn’t go very far without coming to a hill, Fanny would go very slowly and carefully down the hill sidewise, so the Girl wouldn’t fall off. Sometimes she fell off anyway. Fanny would stop instantly and wait until the girl led her to a stump or a rock where she could climb up and get back on.

Fanny was an easy horse to ride and every one loved her and liked to ride her.

One morning in Spring the Girl went out to see Fanny and she had a sorrel mare colt with a white star in her forehead. Mama named her Bonny Belle. Mama’s father was Scotch so Mama liked Scotch names.

You can, maybe, imagine how the Girl loved Bonny Belle. And how she spoiled her. The Girl was in school now and sometimes she rode Fanny to school with Bonny Belle tagging along behind.

When they were home the Girl played with the colt every minute that Mama would let her and the colt was so spoilt that she became so stubborn and mean that she would break every bridle or rope that they tried to tie her up with. And never, as long as they owned her, could they keep her tied up.

Nor never could she be broken to the harness. She always kicked loose and broke things up.

She was a lazy, no good, saddle horse and poked along. No one liked her very well.

I will tell you about Keno. He belonged to my Uncle John who lived in town where he had no good place to keep him, so he sent him down to the river for Papa to care for.

Keno was a beautiful chestnut sorrel. His coat shone like satin and had at one time been a race horse.

He loved the water. He would get in the big irrigation ditch at Joseph and prance up and down splashing water with his front feet. After he came to the river he would get in the river and splash water as high as he could.

He was not a children’s horse. He loved to race. If some one galloped up behind him he would take the bit firmly between his teeth and sink his jaw into his breast and away he went, thinking there was a race on, and it was next to impossible to slow him down.

Papa carried the mail from the Bridge up the river to a Post

Office called Fruita which was up the river from Papa’s homestead. The Girl was sixteen now and was duly sworn in as a carrier of the United States Mail, so she could take the mail on up the remaining five miles for Papa who was always tired when he got home.

One night the Girl rode Keno to take the mail on. Papa said, “Now, Daughter, don’t you run that horse!”

So they started up the river. Every thing was fine until they came to a long smooth bit of road. Now the Girl was a splendid rider. She had ridden almost all of her life and had ridden many horses. She had run races with the Boy and she had even ridden a number of horses when they bucked. So, I am sorry to tell you she thought she knew more than Papa. So she leaned forward in the saddle, eased up on the bit, and kicked Keno in the ribs, and they were off. What fun it was and how good the breeze felt in her face, so she loosened the reins a little more and Keno gained some more speed. So up the road they flew. At last the good road gave out and became rocky, crooked, and full of ruts. So she pulled on the reins so he would slow down and not fall and hurt himself and the Girl. Keno settled his jaw more firmly on his breast and never slackened his pace at all. He didn’t get to run often and was in no mind to quit now. The Girl’s arms were tiring and the road was getting worse. Around the curves Keno went at full speed.

The Girl jerked on the reins and began to be afraid. She pulled and pulled. Finally the road began to climb and the Girl pulled on one rein until she got Keno out of the road onto the steep hillside where he at last came to a stop.

It was a good lesson for the Girl. She learned that Father Knows Best. And she never ran Keno again.

When the children were small they were so glad when spring came. They use to hunt the flowers that first bloomed. The bright yellow fragrant buttercups, yellow bells, beautiful white trilliums, and the just as beautiful white Dutchman’s breeches with their delicate lacy foliage. They found lovely wild violets, much larger than the blue woods violets and the cheery Johnny-jump-ups. These violets grew only where it was quite damp along the river bottom land. Some were pure white, some were a beautiful yellow and the third variety was blue.

Along the hillsides among the overshadowing trees anemones grew. They varied from pure white to a delicate lavender shade. We called them wood’s flowers until someone told us their real names.

Along the open hillsides, among the rocks were chicken pips. Some called them shooting stars. Whatever they were they had a delicate fragrance all their own and were very perky little harbingers of Spring.

Wild purple sweet peas, blue lupine, deep blue larkspur and blue Canterbury bells grew in abundance over the hillsides and down in the dales. A little delicate lacy white flower which had a red stem and lacy foliage grew along the banks and rocky hill sides. We called them baby flowers but that was just one name for them.

Up the river several miles, in the Spring we found deer tongue lilies. Beautiful yellow flowers with a rare perfume. Also there were Deers-head orchids. Short stemmed, lavender in color and exotic in formation.

June brought the lovely rose, and the syringa. Or as some call it, mock orange blossom.

Along the river in the summer grew a yellow flower that we called snap dragons but later learned they were of the (mimlus?)family

The hillsides became a flaming yellow with the bold, brazen sunflowers, later in the Spring. Scattered among them were wild phlox and ragged robins.

There was a quite lonely blue flower which grew lavishly in later summer, along the river. But they were not a popular flower as they smelled exactly like a skunk. The children called them skunk flowers.

In the Fall purple asters and golden rod brightened the roadsides.

Mama loved flowers so much and the children tried to please her by bringing bouquets to her as long as there were any flowers blooming any where.

Mama loved birds almost as much as she did flowers and she taught the children their names and taught them never to kill the harmless ones.

They watched for the first robin to appear. When the robins came Spring could not be very far behind. They nested in the pine trees in the yard and sang their sleepy, chirpy, songs at daybreak. The children awoke to this song and it was part of their life. The hills on the east were still in shade but sunshine could be seen on the hills on the west. The air was cool and sweet and it was fine to be up this time of day.

The same robins came year after year. One had a white feather in her wing. She was not afraid of us and I think she thought of us as her

friends. Many years she came back, then one spring we watched and watched for her but we saw her no more.

Soon after the robin came the bluebird and the meadow lark with his beautiful liquid song. Mama and Papa felt sad when they heard the meadow lark’s song for the day their little boy died, just as he died, a meadow lark, the first one of the year, lit on the cabin roof and sang his roundelay. Maybe he was trying to give them hope for a happier time.

Soon after, the woods and trees were full of our feathered friends. There was the phoebe bird whose song sounded like they were calling to Phoebe. There was a cat-bird who made a plaintive “mew”. It sounded so like a cat that the Girl thought surely one of her beloved cats were lost in the woods.

Orioles and canaries in their bright coats made the woods gay, flashing here and there. The raucus blue jay was also a bright sassy fellow who scolded every one he saw.

Mama always had pretty flowers in the yard and the humming birds came to get honey from the flowers. They stuck their long bills down the throats of morning glories and other flowers and shirred their wings to hold themselves in one spot like helicopters do. They flitted swiftly from one flower to another. The Boy found one of their nests in a syringa bush down by the river close to a high bank. The nest swung on a branch over the swift river. They wondered how the little birds learned to fly without falling in the river. Not many people came here. The nest was very small, not bigger around than a silver dollar and the eggs were so small that the children wondered how a bird could come out of so small an egg. There were two eggs. The baby birds weren’t any larger than house flies.

There were so many birds that I am afraid that I cannot remember them all. There were the chickadees with their

chickadee-dee-dee song and the brown onsel, a pert little bird with his tail in the air, which stood on a rock in the river and teetered up and down incessantly. The children always called them teeter snipes.

Kildeer skittered along the meadow trails on their long legs.

Along the river the king fisher sat on a dead tree limb waiting patiently for a fish to get in his line of vision. He then dove cleanly, caught the fish and took him back to eat. He was a blue and white, rather large bird with a crest on his head and a raspy little song in his throat.

The little brown wren with its stubby tail in the air flew from tree to tree in the woods.

And of course the crows with their raucus caw, caw, cawing. And the magpies with their beautiful long tails. They flew around over the ground in front of the horses and acted like they wanted to get run over.

The red headed wood pecker and his cousin the sapsucker hopped up and down tree trunks with their sharp long claws holding them on.

The big brown woodpecker, called a flicker, made a rat-a-tat-tatting sounding like a machine gun as they bored for grubs in rotten wood or bored out a hole in a tree for a nest.

The big round eyed hoot owl who-who-whooed in the woods at night. It was a spooky sound. They caught Mama’s chickens so the Boy and Papa killed them whenever they saw them. One night Mama went to the chicken house to get a hen to kill for dinner the next day. She had a lantern and she held it up to see which hen she wanted and there sat a huge owl with his big, round, yellow eyes gleaming in the dark. She went and got Papa and the Boy, and the Girl tagged along too. Such an uproar as you never did see. The chickens got scared and flapped their wings and squawked at the top of their voices. The dog barked. Papa yelled directions to Mama and the Boy. Finally Papa got the shot gun and they got the owl cornered and bang!!! went the shotgun and the owl killed no more chickens.

There were the blood thirsty chicken hawks too. When they sailed over head all the hens set up a great kaduck! kaduck! kadocket! at the top of their voices and all the rest of the chickens ran for shelter. The whole family learned to shoot and kept the hawks pretty well shot down.

On hot summer nights the family sat out on the steps of the porch and listened to the katydids chirping and watched the night hawks flying. They weren’t really hawks, and they caught no chickens. They were a sort of cousin of the swallow. They were very graceful in their swooping around. They were catching all sorts of bugs and flying moths and other insects, as they swooped around uttering a sort of cry.

Many years later, after the Girl grew up, got married and moved away, she use to come back summers with her little boy Wayne. Papa was a grandpa now and he and Wayne always loved each other very dearly. Every night they would watch the black bats and these night hawks which were also called bull bats. Grandpa, Wayne’s grandpa,

not yours, use to sing Wayne a song which went like this: Away down south on the Yankte Yank

A bullfrog jumped from bank to bank He split himself from limb to limb Because he had no clothes on him.

Then Grandpa got to singing the first line, then Wayne would sing the next line. The next time Wayne would say, “My sing!” and he would sing the first line and Grandpa the next etc. So they sat in the warm dark, singing, smelling the nice summer smells, listening to the bull bats little call, and the katydids and all the other summer sounds, until Wayne’s grandma told them it was time for bed.

And this is all of the bird story.

There was much to be done in the spring. Every one had to work.

Papa worked long and hard plowing the ground with a team of horses hitched to a plow that had to be held in line by two handles. He had the lines over his shoulders and used his hands to hold the plow in line and to guide the horses as he walked behind the horses in the furrows.

When at last he had the large fields plowed they had to be harrowed. Then he walked with the seed grain in a bag on his shoulder and scattered the seed by hand. The seed had to be harrowed under then rolled with a home made roller drawn by the team. Mama and the children had to work hard with the garden and chores while Papa put the crop in.

The cows must be milked. They use to have to hunt the cows in the evening and bring them in. They would hide out. The Girl, when she grew older, had to get on her horse, take her dogs and go find the cows. One wore a bell. She would stand real still in the bushes where they were hiding, so that the bell wouldn’t ring. The girl would send the dog around until he found them and “heeled” them (bit them on their heels) until they started home.

The pigs and chickens and sheep had to be cared for. And the garden put in which was a lot of work. Potatoes had to be cut up in sizes right for planting. One person dug the holes while another came along and dropped the potatoes in. Then they had to be covered and patted down with the hoe.

All sorts of vegetables had to be planted in rows. Then when they came up they had to be hoed and watered and the onions and carrots had to be thinned so there was work for every one. The weeds had to be

pulled up the rows only.

There was fun too. When the crop and garden were in and the high water had gone down the whole family use to go fishing. Fishing was good in those days so they always had plenty of fish.

The children played along the river. They hunted Indian arrow heads on the hillsides and along the river. I will tell you about the Indians later on. They hunted pretty rocks along the river and on the hill sides.

The children rode their ponies to the neighbors and played with their children and their children came to “spend the day” with them. Later the berries came on and had to be canned and the children helped pick berries. The Girl did not like to pick berries and was very naughty I’m afraid. She wanted to go home. She had to get a drink. She didn’t get many berries in her pail but she ate as many as any one when winter came.

Summer went by quickly. They use to go down and paddle around in the river. There wasn’t enough water to swim in. But it kept them cool.

Mama made jam and jelly and preserves for winter. It smelled so good when it was cooking. We always got some when it was cooled to eat with Mama’s wonderful home baked bread and fresh butter.

Nothing could have tasted better.

Along about the fourth of July they had their first mess of peas out of the garden, the first mess of potatoes. They dug down in the hills of potatoes until they found a mess of potatoes not much larger than marbles. Mama boiled them and creamed them. And the little new carrots came on about now too. Mama scraped the fingerling carrots, cooked them and seared them in a little milk and butter heated. They were most delicious. We always tried to have one first fried chicken for the fourth too. We lived on an austere fare during the winter months but we lived like kings during the summer and fall months. Nothing, now, ever tasted so good as the first fruits of their hard labor tasted in these by-gone days.

It was real warm now and they had moved their beds out in the yard. The Boy slept under the pine trees on the ground. Mama and Papa and the Girl slept in a large open shed where they kept wood. The cabin got very hot and stuffy and it was wonderful to have the summer breeze blowing around them, to hear the katydid chirping and the night

birds crying.

Every minute of every day was full and overflowing and before they knew it it was haying time. Then every one worked hard.

Neighbors exchanged work, so Papa was gone part of the time helping others, then came the day when neighbors came in and helped get their hay up. The Boy ran errands, drove derrick and drove a wagon. The Girl got vegetables and helped Mama cook and feed the men and wash dishes and helped with the chores. It took two or three weeks and when it was over every one was tired. The horses were tired. But it was fine to have the hay in the barn and stacks and to know that better times were ahead. The cooking had been such hot tiresome work and the house got so hot but now every one could rest and about this time the huckleberries got ripe!

Let me tell you about our huckleberry expeditions. We went every year as soon as we could get away after haying. It took them several days to get ready. They had to irrigate the garden good. Papa had to see that the fences around the garden were fixed. So much to do to be ready, and then, those berries!

It was an amazing life.

Duane

Just beautiful, if not for the stories history would be lost, a beautiful upbringing and family.