~

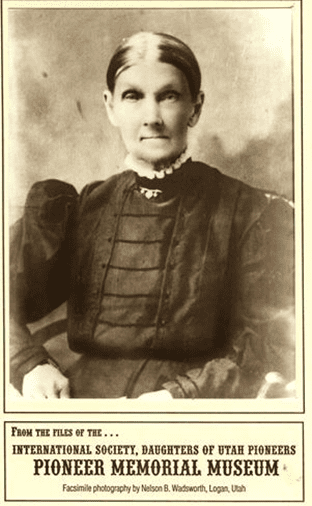

Hannah Maria Goddard (1828-1919)

Wife of husband of 2nd cousin four times removed.

At 18 years old, Hanna first departed in 1846, but she grew weary and returned to Ohio. In 1861 she journeyed the Trail again and settled in Salt Lake City, UT.

Story offered kindly by a distant cousin, Andrea Auclair. See her blog Between The Lines: Family & History

The first time I heard a bit about Hannah’s life, I thought it had to be wrong. It was on an anti-Mormon website. But the story checks out, from multiple sources including BYU.

Hannah was the eighth of nine children born to Percy Amanda Pettibone and Dan Goddard in Schuykill, Pennsylvania. The oldest, Dan, was nineteen years older. She was a little girl when they moved to Charleston, Coles County, Illinois. In 1837 her cousin Lorenzo Snow visited their home while serving on a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Her parents converted, as did her 24-year old sister Adaline and 10-year old brother William. So did little Hannah, who was nine. Adaline was married with two children at the time.

Hannah had just turned 13 when her father died in July 1841. Maybe she and her mother moved to Nauvoo right away. Percy was on the city’s tax index in 1842.

Adaline had a third child 1839, but then separated from her husband around 1844. Maybe religion played a role, as he did not join the Church, and she wanted to gather with the Saints.

Single women were at a tremendous disadvantage. There were few options for supporting oneself, and even fewer if one had children. Women also gained status by marriage. Marriage was – and is – especially important in the LDS Church. In the beliefs of the church, one can only enter the highest level of heaven by being a “worthy priesthood holder,” a male church member in good standing, or for women, by marrying a worthy priesthood holder.

So when cousin Lorenzo Snow offered to marry her, it was probably a welcome offer. Adaline was 33 with three children to support. Lorenzo was a bit unusual as he was a bachelor until he was 31, and entered into polygamy all at once. (In contrast, most men taking a plural wife were already married and had to face talking to their wives about bringing a new wife into the home.)

The records are complicated and differ as to dates, but some say Adaline wasn’t the only one to marry her cousin on her wedding day. Her 17-year old sister Hannah may have. Sisters were often married as plural wives to the same man. Historians Holtzapfel and Hedges say both married Lorenzo 19 Jan 1845.

It was a chaotic time as the prophet, Joseph Smith, was dead; the Saints were involved in what would be a multi-year mass exodus to Utah and the church was in a succession crisis, with families often split apart by individual decisions about whom to follow.

February 1846 Lorenzo led a family party of seven in two wagons out of Nauvoo. With him were wives Charlotte and Harriet Squires, Sarah Ann Pritchard, Adaline’s two younger sons from her first marriage — and Hannah. Adaline, who had just discovered she was pregnant, stayed behind with her mother and 12-year old son.

Brigham Young wanted to move everyone outside the United States and ideally, right away. But realistically, moving some 12,000 people, many impoverished, on a trip that took wagons and teams of oxen and provisions to last two or three months took money. The church didn’t have it nor did many members. A series of way stations were established in Iowa and Nebraska, where the Saints hastily built log cabins and planted crops for those who would come after them. Men such as Lorenzo Snow were appointed leaders of these communities. The Snows would stay almost two years in Mt. Pisgah, Iowa. But first, there is their own exodus story.

They managed to travel nine miles on their first day and sewed a couple of wagon covers together, which they made into a tent. This was their shelter on freezing February nights. Lorenzo wrote of their circumstances:

There were a hundred families gathered in there before us and now others were constantly arriving. We had been but a few days in camp when we had to put up with the inconvenience of a snow storm. The weather turned severely cold and the Mississippi froze so hard that teams and heavy loaded wagons crossed over in perfect safety.

Although they suffered from the cold, they celebrated the hard freeze of river as it helped them get away. Lorenzo wrote of returning to Nauvoo “a number of times” to check on his family left behind, and made arrangements for them to be brought to him in spring. They broke camp on March 1st, and traveled slowly, with men stopping to pick up day labor to buy provisions for their families. It took them a month to travel 110 miles. Lorenzo wrote of mud and the balkiness of his horses. He exchanged them for a team of oxen, but finding food for them was difficult.

They rested a few days, and when they moved on it was very rainy and muddy and they had several creeks to ford. When they were 15 miles from the next camp, the axel on one of Lorenzo’s wagons broke. “It was then raining hard and quite cold,” he wrote. “We immediately pitched our tent and made a good hickory fire. I then went back to my wagon that I had broke to fix some plan to get Sarah Ann [who was sick] to the tent, for she rode in this wagon and was so feeble she could not walk. The water and mud was very deep and we could not get to the wagon without wading.”

They were fifteen miles from camp and nine or ten miles from the nearest house, and Lorenzo was not a mechanic. Fixing the axel did not seem promising. However, a man who had been a stranger for whom Lorenzo had done a favor happened to come along, and happened to be a wagon maker. In the next few days, the wagon was repaired and they were on their way again. But it couldn’t be so simple. One of the wagons became stuck in the mud. They had to take everything out and carry the items many yards to find a dry spot to set them on. They had a dinner and breakfast of dry crackers as they could find no wood for a fire.

When they finally reached camp it was in a place with timber and “an abundance of grass” for the cattle. This greatly lightened the mood and gave everyone a good rest. After a short time there, they were on the move again. In May, they stopped to build houses, fences, and plough the ground for crops. This was a place they would call Mt. Pisgah, one of the way stations.

In June Lorenzo fell deathly sick. He was sick for several weeks and it was thought he would die. It was at this time that Adaline and her mother and son arrived from Nauvoo. The family was offered a home to move into, which was most welcome after three months living out of a tent. That summer, illness and death were rampant. Lorenzo wrote that there were few well enough to help the sick and bury the dead.

In early September, Hannah decided she had enough. She wasn’t the only one. Porter and Calvin Squires, cousins of his wives Charlotte and Harriet, “had got uneasy,” in Lorenzo’s words, and wanted to return to Ohio. “I tried to reason upon them the impropriety of leaving the church,” Lorenzo wrote, “and promised them a home and fare as good as we had so long as they would continue with the saints, but it was all to no purpose, so I let them go.”

Hannah, whom Lorenzo described as “a member of my family” left “contrary to my council and went back among the Gentiles [non-Mormons] thro’ the persuasions of her mother.” Percy arrived at Mt. Pisgah with Adaline in June. By early September, she’d encouraged Hannah to leave. But there was much more to it than discontent. There was something major that Lorenzo left out. In September, Hannah was three months pregnant, but the baby was not his.

Hannah had gotten involved – fallen in love, one hopes – with Joseph Ellis Johnson.

Scandal

Joseph was 11 years older and married to Harriet Snider when he became involved with Hannah. He was a New Yorker who was an early convert to the church, being baptized in 1832. He became a good friend of both Brigham Young and Joseph Smith. He came from a remarkable family of 16 children, and would lead an amazing life. Five of the Johnson brothers brothers went to Utah.[1]

His July 1848 diary reveals a lively person who enjoyed some worldly fun. He wrote of enjoying a “grand fandango” with friends, playing euchre, drinking cherry bounce and Irish whiskey,” and dancing with a heap of pretty gals till 2 o’clock in the morning.”[2] He mentioned a lot of socializing with alcohol involved. He made one reference to seeing his wife Harriet, waiting at home.

Apparently, when Hannah left Lorenzo, she moved in with Joseph Ellis Johnson. Lorenzo wrote that she went to live with Gentiles, but Joseph was a church member. What he may have meant, however, was that they were living amongst the “Gentiles,” obviously not part of the gathering of Saints in camps preparing to journey to Salt Lake.

In 1849, due to his actions with Hannah, Joseph Ellis Johnson was stripped of his priesthood authority – his good standing in the church. He was brought before a church council at which Brigham Young presided. Testimony was recorded as follows:

Orson Hyde: There is a matter of Bro Johnson to be laid before the Council….his priesthood was required to be laid down until he came here. A Miss Goddard, wife of Lorenzo Snow became in a family way by Bro Johnson – she was living in his house – we deemed it improper for her to be there – he sent her away to a retired place – she was delivered of a child – she is again living in his house in Kanesville – he wishes to retain his fellowship in the Church. He says he has [met with] bro Snow and he was satisfied.

Joseph E. Johnson: I am come purposely if possible to get the matter settled and atone for the wrong I have done—I have neglected to lay it before you before this –bro Hyde’s statements are all correct – true – all I can do is beg for mercy – I became acquainted with the girl & the consequences are as they are – I saw bro Snow at Kanesville and he was satisfied – I am come here to atone for the wrong I have done.

(Spelling corrected.)

The secretary recorded comments that made it clear that Joseph was not trying to excuse his conduct.

“I never heard any conversation that said it was right to go to bed with a woman if not found out – I was aware the thing was wrong.”

Reports state that Lorenzo released Hannah from her sealing to him. Hannah and Joseph were not sealed together until 1861 after they had six children together. This is because the two lived far from the only temple where their marriage could be recognized – in Salt Lake.

Although he’d fought to retain his church membership, Joseph didn’t seem to be in a hurry to move to Utah. He was busy in Iowa and Nebraska as a newspaper owner and editor, businessman, postmaster and politician. Joseph also took a third wife, Eliza, one of the English coverts. She was 16; he was 39. Her first child was born in 1857.

He finally moved his youngest wife to Salt Lake City in 1860. He brought Hannah and the rest of his family in 1861. After a few years in the city, he bought land about 70 miles outside and called it Spring Lake Villa. There he stared a store selling seeds and gardening supplies, a print shop and newspaper.

. A few years after they settled in Spring Lake, Joseph wanted a warmer climate. His son Charles wrote of their 1865 move to St. George, in a long train of wagons with the printing press and contents of the store, ready to set up shop in this new place. They lived in tents until he could get a house built. They were twelve miles from the Arizona border and 360 miles from any town of consequence. There he again opened a garden and nursery supply store and in 1868 continued newspaper publishing. In 1870 he also founded the Utah Pomologist and Gardener, a monthly publication. His son wrote that their home was the only one with a library, that his father owned several hundred books.

Hannah and Joseph had two more children after their marriage was official, in the eyes of the church, at least. Hannah’s last child was born in 1864, a namesake daughter who died in infancy.

St. George may have been isolated, but for several months Dr. C.C. Parry, botanist at the National Herbarium in Washington D.C., stayed with them while he scouted for new plants, naming several after Joseph.[1] This had come about because Joseph sent letters and plants to Dr. Parry and peeked his interest in fieldwork in Utah. Next came Dr. Edward Palmer of the Smithsonian Institute, who excavated Indian mounds.[2] Brigham Young built a winter home next-door to his old friend Joseph and came on a regular basis.

Even with all his businesses, Joseph found it hard to make a go of things in St. George and to support his large family. Around1880, he was happy to be called to a mission to settle part of Arizona, along with his nephew Sixtus Ellis Johnson, and two of his brothers, Joel and Benjamin. According to his son Charles, he saw it as a fresh start.

As early as 1849 when members of the Mormon Battalion returned from California by way of Arizona, Brigham Young dreamed of Mormon colonies raising sugar cane and cotton there. It was not practical at that time. In the 1870s Brigham revived the idea with vigor. European converts continued to stream into the Salt Lake Valley, where the good land was already taken, and Brigham said the city was overcrowded. He also said it was the duty of the faithful to build up the kingdom of God by spreading it out. Another motivation was Brigham’s desire to convert the Indians.

Colonization in Arizona was not successful in Brigham’s lifetime, but the next president, John Taylor, wanted to continue Brigham’s initiatives. In 1878 Snowflake was founded and became a success. Life was hard there, though, and travel to Salt Lake not for the feint-hearted. David Udall described his journey from southern Utah to St. Johns, Arizona saying, “Most of the country through which we passed was desolate beyond belief.”

Joseph was 63 when he was called to Arizona, and colonization in such a hard place was better suited for a young man. But he was game. His oldest brother Joel was released from this mission call due to age, however, before he could make the trek. There were some 500 colonists who moved with Joseph.

Joseph had two children in Arizona by his third wife, then died of pneumonia in 1882 when the youngest was just two months old. His family was left in straightened circumstances. Hannah was 54 and all of her children were grown.

All the wives relied on the support of grown children.

Hannah was still in Maricopa County, Arizona in 1900. Hannah lived with her daughter Josetta, Josetta’s only child, Stella Ross, who was 17, and her 10-year old nephew, Robert Cassidy. Robert was the son of Hannah’s daughter Julia, who divorced her husband in June 1895 on grounds of abandonment. (She remarried in December.)

Joseph Ellis Johnson’s first wife, Harriet, also stayed in Arizona and when she died in 1905 was buried beside him. The younger third wife, Eliza, returned to Salt Lake City where her oldest son Charles supported her. [3]

Sometime after 1900, Hannah and two of her daughters, Josetta and Julia, moved to San Diego. After Josetta died in 1908, Hannah made her home with Julia. Only one of Hannah’s eight children, Christianna, known as Christie, would outlive her.

On the 1910 census Hannah lived with Julia, Julia’s husband Thomas Jensen, a dairy rancher, their four children, and two of Julia’s children from her previous marriage, Robert and Philip Cassidy. A Swedish farmhand also lived with the family.

Julia was killed in 1918 when the car her husband was driving was struck by a San Diego & Arizona train. Hannah died almost exactly a year after her at 91, laid to rest after a long, challenging pioneer life.

~

Sources:

Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach. “The Iowa Journal of Lorenzo Snow,” BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 24, Issue 3, Article 3, 1984.

Cluff, Judy Harris. “The Life Story of Julia Hills and Ezekiel Johnson,” 2008, posted on Ancestry.com.

Holzapfel, Richard Neitzel and Andrew H. Hedges. Within These Prison Walls: Lorenzo Snow’s Record Book, 1886-1897, Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Books, 2010.

Johnson, Charles Ellis. Short Autobiography of Charles Ellis Johnson, Found in his papers at his death in 1926. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=906122

Johnson, Joseph Ellis. Diary No. 1, 1848, Joseph Ellis Johnson Papers, University of Utah, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=906122

Lindbloom, Sharon. “A Mormon Detective Story,” Mormon Coffee – It’s Forbidden But It’s Good blog, https://blog.mrm.org/2015/04/a-mormon-detective-story/

Ricks, Joel. “Mormon Colonization in Arizona (1950). Joel Ricks Collection, Paper 11. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/19682953.pdf

[1] Charles Christopher Parry (1823-1890) was described as “one of the most genial and loveable of naturalists.” A surgeon by training, he spent over 30 years collecting plant specimens, especially in the Colorado Rockies and along the Mexican border.

[2] It’s rather curious that Charles Johnson described this as Palmer’s focus. Palmer (1831-1911) became known as the Father of Ethnobotony. It must have been interesting for him to stay in a house with three wives and over 20 children.

[3] There is speculation on the Benjamin Franklin Johnson Family Organization website that she became the eighth wife of his brother Benjamin on 3 March 1885. Certainly, that would give her financial support. But I think that’s unlikely. Charles said he supplied his mother with a house and that after a brief time living in the St. George house, she remained there for the rest of her life. He does not mention a marriage, nor does her obituary.

[1] His brother Benjamin had 46 children with seven wives. Joel had five wives and 31 children. Joseph Ellis had 29 children with his three wives. George Washington Johnson had three wives and 18 children, and William had 12 children with his one and only wife! That’s a lot of cousins for Hannah’s children, and that’s just from these brothers. Benjamin would serve 14 terms in the Utah Territorial Legislature. Joseph Smith took two of the brothers’ sister as plural wives.

[2] He’d been married for eight years and had four children when he wrote this. Cherry bounce was a cherry-flavored alcoholic drink that was a favorite of George Washington.

~

“By learning about their lives, we gain a deeper understanding of our heritage, and the strength of the women who came before us.”