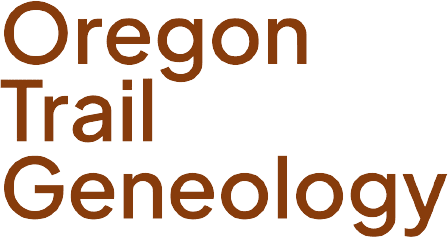

Frank & Rosalia Fisk, circa 1880

I’ve not encountered many people who aren’t intrigued, and often captivated by, images of family taken in the mid to late 1800’s. These glimpses of family provide an empathetic moment where we might briefly experience an instant of their perspective, to momentarily place ourselves in their position, to imagine what their lives may have been like.

Many of the photographs we find while doing family research are “staged” photographs of individuals or family. Early photographers often employed background props, and the subjects tended to dress themselves in their “Sunday best.” So while the photographs are intriguing (and often we might find similarities to ourselves or a present family member in a turn of a smile or the set of the eyes), they can also be an illusion. While sparking the historic imagination, we must remember that the portrayal of family members was in part due to the artistic eye of the photographer, as well as the view the family sought to present.

Despite that, there is no question that the photographs create a human bond. These people are family, and their blood flows in you now. In addition to this human bond, and a glimpse in time so long ago, the photographs can often present clues to family research that are subtle and unexpected.

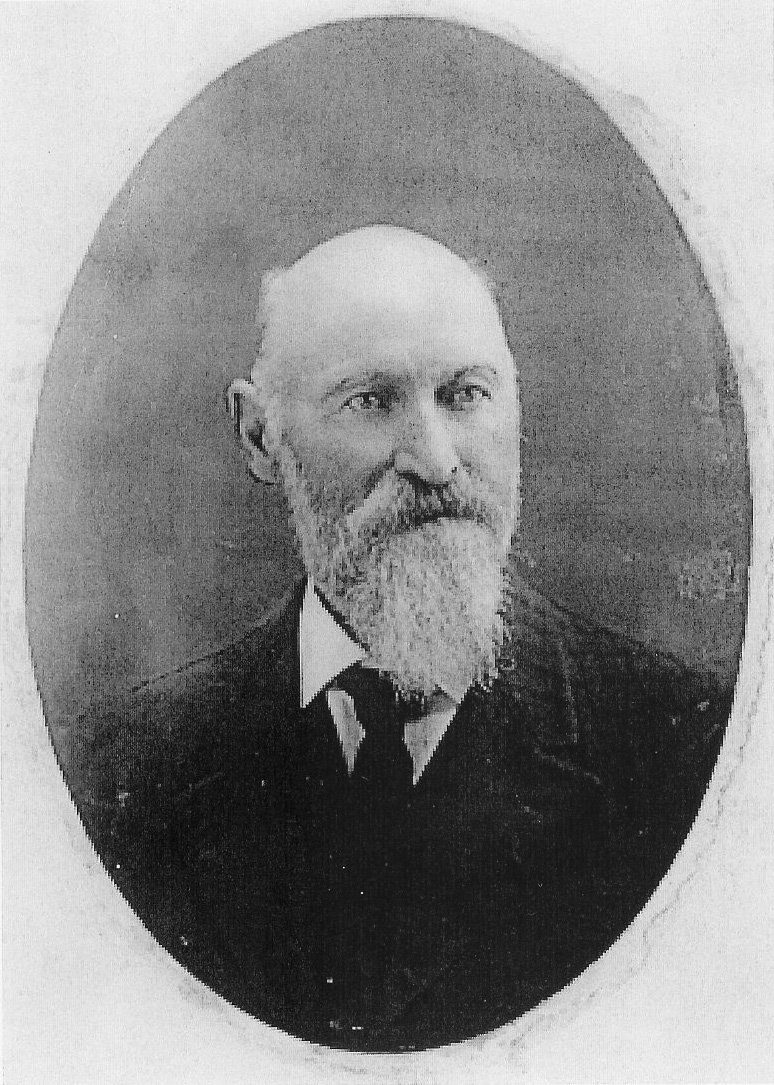

Over time I noticed that many of the family photos I had found were framed in the photographer’s own cardboard frames with their names engraved at the bottom. The American daguerreotypes were the first type of photographs of the 1800’s, the technique invented in France by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre in 1839. Most portraits were take with this technique in the early days, but with the advent of the “wet-plate” negative process in the late 1850’s, photographers had the means to reproduce multiple copies of the image to paper, and thus, commercial prospects arose. The photographer’s personalized frames were part of this new enterprise. Photographers like George I. Hazeltine in Canyon City, and Mrs. C. Haven in Prairie City were two of the leading photographers in the John Day Valley of Oregon. George, and his brother Martin who was also a photographer, traveled widely from California to Alaska photographing people, landscapes, and industry.

Mary Cornelius Wilson Fisk (1856-1935)

Over time, these old photographs were passed from generation to generation, some of them landing in the hands of people fascinated with the past and reconstructing family histories. One day, while researching my family’s Fisk line, I noticed that the middle name of Lydia Wikle (1843-1915) was Hazeltine, and thought how odd that was for a woman’s name. Surely someone with that name was important enough to her parents that they chose to give it to their daughter. I knew I’d seen that name somewhere, so started a search of Lydia’s family, and searched the name Hazeltine. When I found the history of the Hazeltine brother’s as photographers, I searched through my own collection and found Hazeltine photographs of other relatives in my family. But try as I might, I could not discover the reason Lydia had that middle name, or any connection to the Hazeltine family. Family research frequently has disappointing dead ends…

I ran across the name again in Mildred Hazeltine (1884-1966), who had married Linden McCullough and thought I had discovered something. The McCullough’s lineage runs deep through my own, down to my great grandmother Gertrude (Fisk) McCullough. I backtracked Mildred’s lineage to Patrick McCullough (1735-1811), and though I learned he came to America from Ireland as a 15 year old, I was unable to learn anything about his family or connection to the ancient line of McCullough’s already in my family line. It looked like another dead end, for researching family members in the 1500’s and 1600’s Ireland is challenging. It wasn’t necessarily a dead end, but it is a road block I haven’t yet found a way around.

The population of Grant County, Oregon in 1870 was 2,251 (Oregon – Census.gov). Given the large size of the county and the few people living there, the gene-pool, to be frank, was limited in regards to finding a partner. The point then, of this article and the examples of my own research below, is that examining the lineage of your family’s neighbors and associates can lead to important discoveries about your own family.

George I. Hazeltine (1836-1918)

My next attempt was to go through a process that many genealogists follow, one that can be both tedious and unfruitful. Though the Hazeltine’s appeared unconnected to my own family I began to build the family tree of George I. Hazeltine. Having ruled out that any of his children were connected to my family I started backtracking in time. The first step was to discover if he had any brothers, then look to see if any of them or their children were connected to my family. With no discoveries there, I turned to his father, and found no siblings at all. His grandfather however, had 13 brothers. Each brother was researched in turn, looking for children or grandchildren who connected to my family. In the mid-1750’s history of that family I got lost reading about his grandmother, following her lineage, and traced it back to 1619 where I found names that seemed somehow familiar, and ended up connecting them directly to the maternal line of my grandfather Nathan Fisk. From my first blog post you may recall that this is the same Nathan who inspired my love of history and family research when I discovered his photo that hangs in a small Canyon City museum, and who traveled the Oregon Trail in 1852.

This photographer, George I. Hazeltine, who documented the lives of my family and others in the 1880’s, had the same blood coursing his veins that I have in mine, with a common ancestor in the early 1600’s, who in turn created a web of family lines weaving through history to the present. But as George looked through the lens of his camera, he would have had no idea it was his family that stared back at him. Now, some 150 years later, we have access to records they could not have known about, digital data to assemble family lineages. Had they even imagined there were family connections the records they may have used could have been 2000 miles back down the Oregon Trail with families that were left behind; a few generations noted in family Bibles, a few letters, some Church records, all scattered and mostly inaccessible. Our ancestors carried on their lives with friends and acquaintances, but our studies can reveal family connections between supposed disconnected relationships and give us a richer view of our immensely interconnected family, their history, and how they lived their lives.

To learn more about Hazeltine Photography see: George I. Hazeltine and Martin M. Hazeltine photographs, 1866-circa 1920