Many of us who dabble in the history of the Pacific Northwest and the Oregon Trail are familiar with some of the names frequently encountered – Jedediah Smith, Jim Bridger, Nathaniel Wyeth, John Jacob Astor, William Ashley, Hugh Glass, Peter Skene Ogden, Joseph Meeks.

Another name we often encounter is Sublette – the Sublette Cutoff on the Oregon Trail, the Sublette Range in SE Idaho, Sublette Co., Wyoming, Sublette St. in Pocatello, Idaho, Sublette St. in Kansas and Sublette Ave. in St. Louis.

It wasn’t until I found the name distantly in my own family tree that I took notice of the name and investigated the family. What I discovered was a remarkable journey into the fur trade of the early 1800’s.

“Sublette was among the mountain men who journeyed into the Rocky Mountains and other unorganized territories, which were often economically controlled by the joint British-Canadian fur companies of Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company. Both companies competed against the activities of the American Fur Company, founded by John Jacob Astor, who created a monopoly in the American west before 1830.

In 1823, William was recruited in St. Louis by William Henry Ashley as part of a fur trapping contingent, later referred to as Ashley’s Hundred. That was the beginning of a new strategy for conducting the fur trade in response to a change in United States law in 1822. Liquor had been one of the principal currencies traded to Native Americans; such trafficking had been made illegal. The new scheme set up a trapper’s rendezvous, a teamster-drover team operating the freight bringing in supplies and returning with furs, and a corps of trappers making their circuit through the year to traps they had set as team members.

By 1826, Sublette acquired Ashley’s fur business, along with Jedediah Smith and David Edward Jackson. By the mid-1830s, his brother Milton joined as one of five men who bought the Rocky Mountain Fur Company from William and his partners. Sublette retired from trapping after being wounded at the Rendezvous of 1832 in the Battle of Pierre’s Hole. After recuperating for over a year back in St. Louis, Sublette returned to the uplands and founded Fort William, in the foothills east of the South Pass. The fort commanded the last eastern stream crossing at the foot of the last ascent to the floor of South Pass. That was the only route readily navigable by wagons over the Continental Divide.

He sold Fort William to the American Fur Company, which renamed it Fort John. After the U.S. Army took possession, it was renamed as Fort Laramie. Sublette retired to St. Louis, where he died in 1845.”1

There are countless books written about the fur trade, William Sublette, and this critical time period in the settlement of the west. It is not my intent to repeat those scholarly tomes here, for the history is easily available elsewhere.

Intertwined with history is family, and I have long been fascinated with how history impacts family, and families create our history. The impact that William Sublette, and his brothers Milton, Andrew, Pinckney, and Solomon had upon the history of fur trading was substantial. But the impact of that enterprise impacted the Sublette family as well. William in particular was a savoy businessman, and the Sublette family prospered. But history impacts family and there were personal consequences of their success.

The hard life of trapping brought the family wealth, but all the Sublette brothers died young. Milton died at age 35 when stabbed by an Indian. Andrew died at age 45, killed while fighting a grizzly bear. Pinckney died at the hands of a Blackfeet war party in Idaho at age 16. Solomon died at age 44 in St. Louis. William Lewis Sublette died of tuberculosis at age 45, a year after his first marriage.

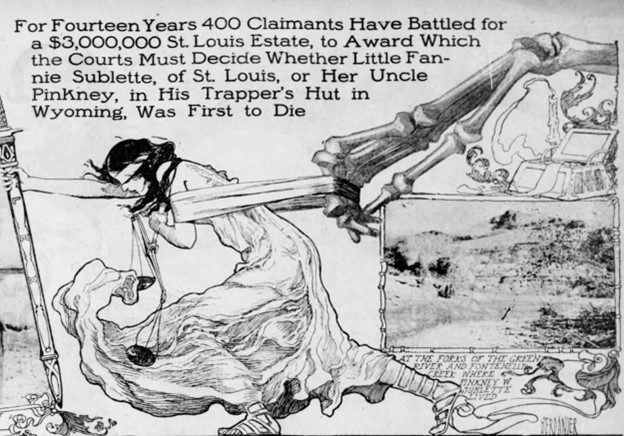

On 28 May 1911 the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published a lengthy story entitled “The Mystery of the Sublette Millions“. I offer it here as a rather stunning example of history impacting family.

The full article, transcribed in its entirety, spelling and grammar intact:

“In all the annals of court procedure there is no case more full of actual mystery, of complex and puzzling questions, of disputed happenings, of fantastical turns and twists than the “Sublette Case” in the Circuit Court of St. Louis, which is soon to be reopened for further hearing.

In this case of many mysteries the ownership of an estate worth $3,000,000 within the city of St. Louis hinges upon whether a solitary grave in a Western prairie was that of Pinckney W. Sublette.

How that grave was found and the intricate windings of the search made for it by a lawyer of St. Louis, how a small piece of broken stone led to the discovery of it when the lawyer, discouraged and weary, was about to give up the hunt, is the strangest part of this amazing story.

In the beginning of the lawyer’s quest there were known just the following bare facts:

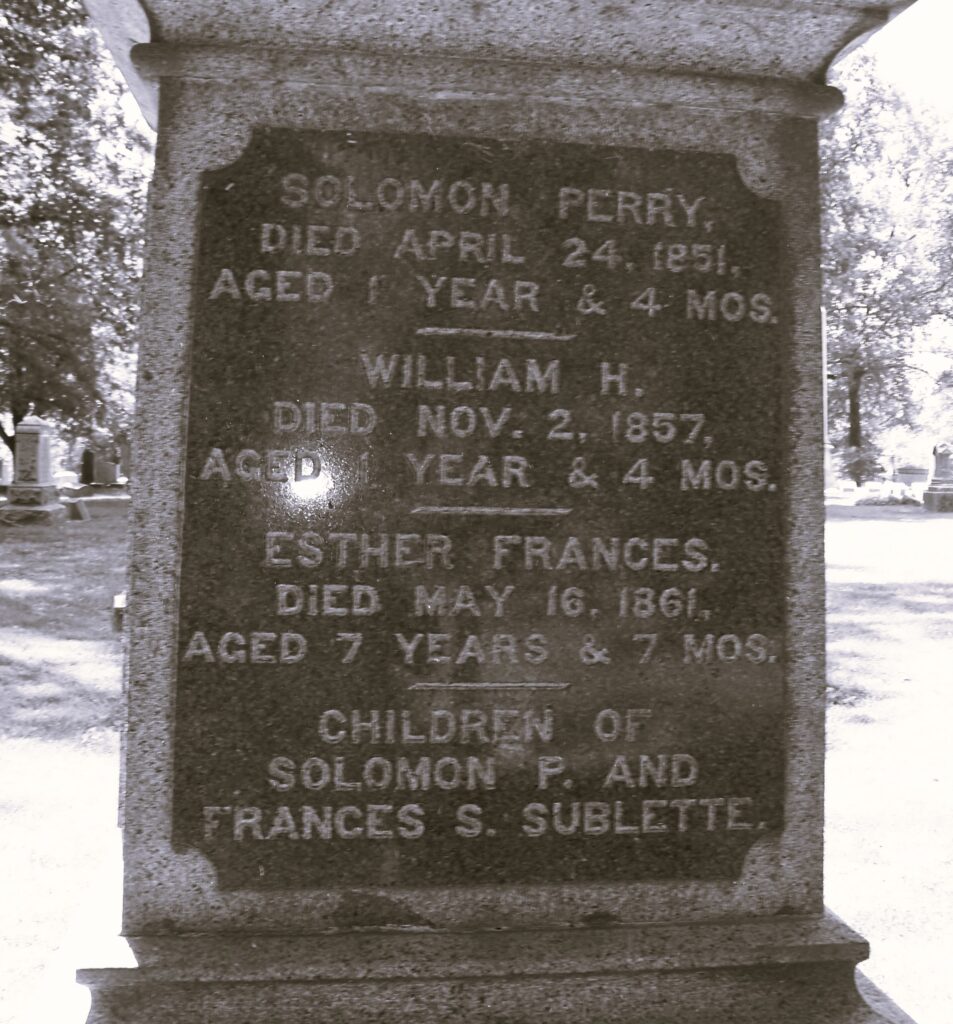

In 1861 the Sublette farm of 250 acres bordered the city limits of Southwest St. Louis. A series of deaths, following quickly one after another, had left Fanny Sublette, a delicate child of 4 years, the sole owner of the big farm. Her father, Solomon Sublette, had died in 1857. Her mother died a month later. Her baby brother died two months after his mother was buried, and Fannie died May 16, 1861when she was 9 years old.

The cause of the sudden death of this child was never determined. She was stricken while eating dinner at a party given on her birthday to her girlfriends and died within an hour. It was given out that some food she ate had poisoned her, but none of those who were eating with her were made sick. There was suspicions and whisperings that were not lessened by the fact that for several years before her death there were bickerings and quarrels among her relatives about what disposition would be made of her estate should she die.

Fannie’s relatives had wrangled among themselves about her custody while she was still alive. One faction had kidnapped her and taken her to New York. There she was discovered by another faction and returned to her home in St. Louis. Echoes of these disputes and of the manner of her death have come down through the years and are hinted at in the voluminous court records that have accumulated in the case in recent years.

Pinckney Became a Trapper.

It was known when Fannie died that her uncle, Pinckney W. Sublette, when a schoolboy in 1829, had gone up the Missouri River with a band of traders and trappers; that he became a trapper and lived with the Indians, and that he disappeared in the wilderness and never returned to Missouri. There were stories that had had been scalped and killed by hostile Indian, but nothing definite was known about that, and no one took the trouble to try and find out whether he was dead or alive.

[Side notes by MG: Contrary to this account, Pinckney’s death was known, as told in Explorations of Jedediah Smith from the book “The Ashley-Smith Explorations and the Discovery of a Central Route to the Pacific 1822-1829 by Harrison Clifford Dale.]

“After a week with the English, Tullock and Campbell, with most of their men, set out northward. Their departure was taken so quietly and their destination left so vague, that Ogden suspected, probably with some foundation, that they were bound for the forks of the Missouri and the land of the Blackfeet, who, as it happened, had been singularly docile this year.568 His suspicions were confirmed when he learned that they had arranged their summer rendezvous for the Flathead country, not far distant from the Three Forks. Tullock was equally suspicious of the designs of Ogden, placing a sinister interpretation on a misfortune which befell him shortly after his departure. Within three or four days of Ogden’s camp, a detachment of his men were suddenly attacked by thirty or forty Blackfeet, who killed three and made off with about forty thousand dollars’ worth of furs, forty-four horses, and a considerable quantity of merchandise.569

567Oregon Historical Society, Quarterly, vol. xi, 371, 373, 374.

568 —Idem, vol. xi, 375. “These people [the Blackfeet] had always been considered enemies to our traders; but about that time [1827-1828] some of them manifested a friendly disposition, invited a friendly intercourse and trade, and did actually dispose of a portion of their furs to Messers Smith, Jackson, and Sublette.”-Letter of W. H. Ashley to T. H. Benton, January 20, 1829, in United States Senate, op. cit.

569 —Idem. Ogden afterwards saw the clothing, horses, etc., of these men. Oregon Historical Society, Quarterly, vol. xi, 378. He was, however, in no way responsible for the attack, as hinted by Sublette to Ashley. Among those killed was Pinckney Sublette, a brother of William Sublette. Five other men were lost in the course of the year. United States Senate, op. cit.”]

As the years went by St. Louis grew and spread and the Sublette farm became worth millions, but the mystery of Pinckney W. Sublette, lost in the Western wilderness, was a cloud upon the title to every foot of ground in what had been the Sublette farm, and the reason for that cloud is this: Under the law, if Pinckney W. Sublette was alive for any length of time after the death of his niece, Fannie, then he was one of her heirs and would inherit one-eighth of the farm, and, if he died unmarried and childless, his share would descend to his uncles and aunts. These uncles and aunts were dead, too, but they had descendants, and these numbering 100 now, would be the heirs today to the interests of Pinckney W. Sublette in the estate.

In 1897 these heirs foregathered in St. Louis and retained Thomas B. Crews, former Probate Judge in St. Louis, to find out for them whether Pinckney W. Sublette died before or after the child Fannie.

Crews had only this fact to work upon, that Pinckney w. Sublette had gone 68 years before, to the headwaters of the Missouri River, and that he was for years a trapper somewhere in that country. That was all. There was not another clue. It was supposed that he was dead, but it was not known to Crews or the heirs where or how he had died or where he was buried.

Crew Goes on the Trail

Out then into the vast territory known as “The Northwest” went the lawyer upon his quest which would seem an almost hopeless one, made yet more discouraging by the story of John S. Shaw, who said that in 1842 he was told by William L. Sublette, elder brother of Pinckney, and himself a trapper, that Pinckney had been killed by Indians, but Shaw could not remember further details.

For months Crews traveled by railroad, by stage, and on horseback through the states of Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah and on to the Pacific Coast, inquiring everywhere for old settlers, pioneers of early days, who might have known Pinckney W. Sublette. Wherever he would hear that an old trapper was living Crews would go and talk with him. Widely scattered over a territory thousands of mile in extent, he found several aged men who had know Sublette. They described him as a man 5 feet 9 or 10 inches tall, with dark hair and sandy beard, of about 160 pounds weight, and all agreed that he had lived somewhere in what is now the State of Wyoming. Gradually the search narrowed down to Unity County in Southwest Wyoming.

After months of harrowing travel Crews found an old man who had been a pony express rider, and was a ferryman on Green River, Wyoming, in 1865, who said that here he met Pinckney W. Sublette who was very old and who lived alone in a shack on the bank of Fontenelle Creek, about a mile from where it emptied into Green River. This man told Crews he had talked with Sublette, who said he was from Missouri and that he was a brother of William and Solomon Sublette. In 1865, this man said, Sublette had died alone in his cabin and was buried by neighbors in a lonely grave in the open prairie, and, he said, he had seen the grave, which was marked by a stone slab taken from the creek bottom.

The Lone Headstone

This was the first definite clue to the location of the grave, and Crews hastened by stage to the village of Opal and drove out to the ranch of Charles Robinson, seven miles from the mouth of the creek where the grave was supposed to be. Robinson told him that he owned the land in which the grave was, that he had often seen the headstone and wondered who was buried there, and that upon the slab was carved the letters:

P. W. S.

D

1865

Robinson said the gravestone stood on open ground about one hundred feet west of a haystack on the bank of Fontenelle Creek, one mile from its mouth

Crews went to the ranch of Charles W. Holden, several miles nearer the creek mouth. Holden said he often had seen the solitary gravestone and had read the lettering on it and drove Crews to the spot. The haystack described by Robinson was there, but not a stone of any size could be found in the field, the soil of which was a black loam, without even a pebble in or upon it.

The next morning Crews declared he was going to search for the grave again. Holden laughed at him and said it was useless to do so. If the stone was there they would have found it the day before. But Crews went, and he was accompanied by Clarence Howard, Miss Ella and Miss Minnie Holden, sons and daughters of Mr. Holden, and by Miss Cora House of Corrine, Utah, who was visiting at the Holden ranch.

For hours they searched over all the ground up and down the creek bank. There could find no stone and no trace of the grave, and were about to give up the hunt when Crews decided to measure off 100 feet straight west from the haystack and look closer for some depression in the earth. He paced off what he judged to be 100 feet and stopped. He looked down at a spot that he had walked over a dozen times already and he noticed what he had not seen before, a small round hole in the sod. He put his fingers down into the hole and felt a hard substance at the bottom. With a spade he took it out. It was a piece of broken stone about as large as his fist, triangular in shape, but with no letters on it. Looking closer one of the girls found another piece of stone, somewhat larger, lying flat on the surface, 10 feet from where the first piece was found. It had sunk into the sod and was almost hidden by the grass. An edge of the piece of stone fitted exactly one edge of the smaller one found in the hole.

“We will dig here and see what we will find,” said Crews, stamping his heel into the depression from which the smaller stone had been taken. Six inches below the surface the spade struck another stone, lying at an angel of 45 degrees. Crews dug the earth the upper side of it, and, as he lifted it, he saw upon the soft earth where it had lain the impression of some letters. He washed the stone and saw there the carved inscription:

P. W. S.

D

1865

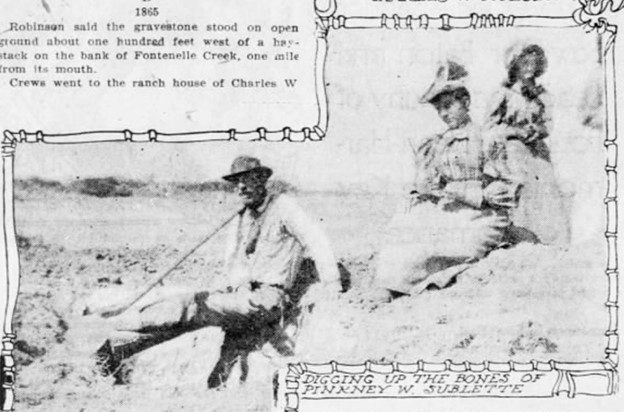

They dug four feet and again the spade struck upon stones. Uncovering the whole length of these they found it to be a double row of flat stones from the creek that had been set up against each other at the bottom of the grave, like the peak of a house roof. This had been the rude stone coffin placed by the pioneer neighbors of Sublette over his body 32 years before. Beneath these stones they found a skull, well preserved, and some bones of the legs, arms, vertebrae and ribs.

This was the end of a long search, and Crews spread his overcoat on the ground, laid the bones upon it and wrapped them up in it and took them to the Holden ranch house. There the bones and gravestone were put into a box and Crews brough it by stage and train to St. Louis and deposited it at the courthouse.

The heirs of Pinckney W. Sublette were called together in St. Louis and Crews made his report. They authorized him to begin suit to recover the estate. Crews did this, and then began the long and costly litigation which has trailed through the courts with varying fortune for the last fourteen years, and which promises to go on many years longer and to go down in legal history with that other chancery case made famous by Dickens: “Jarndyce versus Jarndyce.”

The first suit was brought in the name of three heirs who had been agreed upon by all the heirs to prosecute for them – Thomas Peniston, Dennis G. McCarron and John N. Dalby. It was against Christian Schulde, one of the holders of land of the old Sublette farm in dispute.

Had Sublette a Double?

The trial was before Judge Horatio D. Wood, it having been agreed by both parties to the controversy to waive a jury and have the issues determined by the Judge. At the trial the bones and the gravestone were exhibited in court and handled by the lawyers. Witnesses were brought from the Far West to tell of their acquaintance with Pinckney W. Sublette. The deposition of the five persons who were with Crews when he found the grave and dug up the bones were read to the Court. There was no direct testimony that Sublette had died prior to the death of Fannie Sublette, but Mrs. Mary M. Moore, first cousin of Pinckney W. Sublette, testified that in 1847 his brother, Andrew Sublette, who later was killed by a grizzly bear in California, had told her that Pinckney was killed by the Blackfoot Indians in the West, and that he, Andrew, was in the same fight but escaped. Andrew told her, she said, that he did not see Pinckney killed and did not see his body afterward, but he knew he could not have escaped.

The lawyers for the present holders of the property argued that there must have been two Pinckney W. Sublettes and that the one whose bones were found in the grave and brought to St. Louis was not the uncle of Fannie Sublette. Judge Wood decided that Pinckney W. Sublette died long prior to 1861 and left no descendants, and therefore the claimants who were suing for the estate had no standing in court. The Supreme Court upheld this decision.

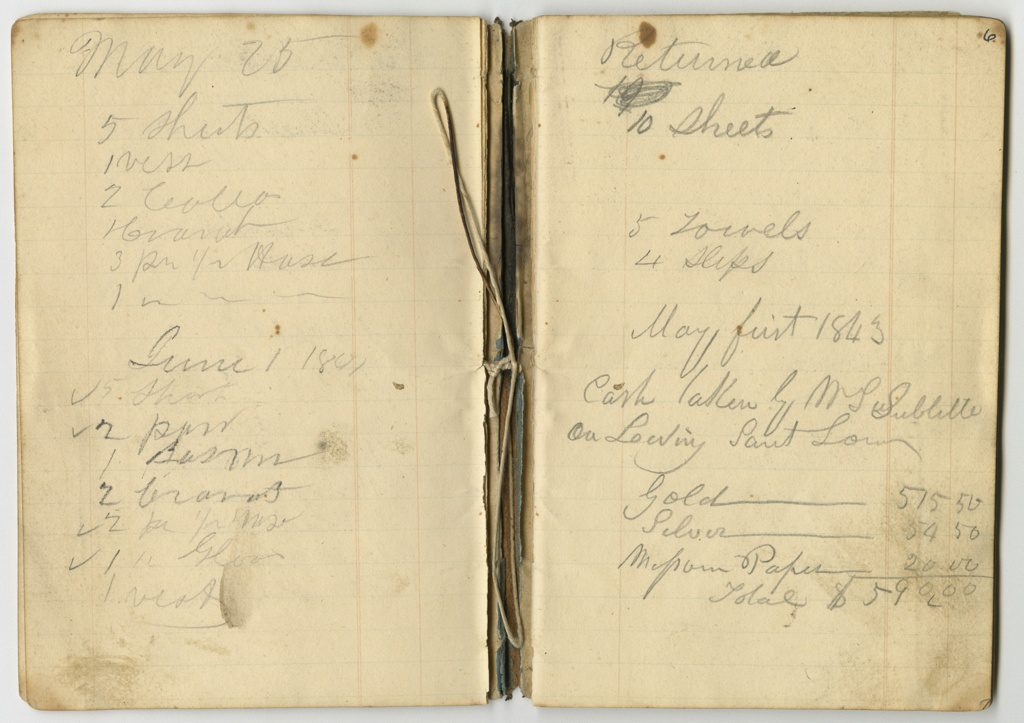

As strange, almost, as the finding of the lost grave of Sublette, the trapper, was the discovery of the will of Solomon P. Sublette, the father of Fannie and brother of Pinckney W. Sublette. Soon after the adverse decision by the Supreme Court the lawyers for the heirs of Pinckney W. Sublette received by mail and old and time-stained will, to which was subscribed the name of Solomon P. Sublette and as offered for probate, but was rejected by Judge Rassieur for lack of proof of genuineness.

Then occurred another strange happening in this case of many surprises. E. C. Smith of Meade, Kan., one of the witnesses to the will, had never heard of the controversy over the Sublette estate, but he was working out his “family tree” and he wrote to a firm of lawyers in St. Louis for certain information about one of his ancestors who lived there. The lawyers happened to be one of the firms engaged in the Sublette litigation. When they saw his name, they wondered if he could be the E. C. Smith who had witnessed the will of Solomon Sublette. They wrote to him and learned that he was the very one. Later he came to St. Louis and testified in a suit to establish the Sublette will, and, in 1907, Judge Allen of the Circuit Court rendered a decision making valid the document as the last will and testament of Solomon Sublette. The will was as follows:

Will of Solomon Sublette

In the name of God and man, I, Solomon P. Sublette of County of St. Louis, State of Missouri, dispose of my property as follows: First, that all just debts to be paid; second, bequeath to my beloved wife, Frances, all my personal property and real estate in the counties of St. Louis, Cole, Jackson and elsewhere, and at her death bequeath all said property to my daughter, Esther Frances (Fannie), and if she die single and unmarried and without issue, I bequeath said property to my next of kin on my father’s side.

This is my last will and testament. In witness whereof my hand and seal this 15th day of April, 1856. On farm near St. Louis, Missouri. SOLOMON P. SUBLETTE

Witnesses: E. C. SMITH, JAMES C. THOMPSON

Since then, other suits have been filed and soon are to be tried in the Circuit Court. The heirs of Pinckney W. Sublette are confident they will establish their right to one-eighth of the Sublette farm.

The property involved is bounded by King’s highway, old Manchester Road, Sublette Avenue and the Missouri Pacific Railroad tracks. Among the owners of property whose interests will be lost if the decisions in the pending contests are in favor of the plaintiffs are George Q. Thornton, the Carondelet Foundry Co., former Gov. David R. Francis, Congressman Bartholdt, the Pattison Avenue Baptist Church, the Board of Education of St. Louis, the Right Rev. John J. Glenson, Archbishop of the Catholic Diocese of St. Louis, the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association, Hydraulic Press Brick Co., Meyer Real Estate and Investment Co., St. Louis Smelting and Refining Co., Evens and Howard Fire Brick Co., Sanders Press Brick Co., American Brewing Co., Scanion Realty and Investment Co.

Many Claimants to Estate

Among the claimants of the property are Thomas Peniston, agent Eagle Packet Co., St. Louis; Daniel G. McCarron 3824 Eade Avenue; Mrs. Mary Whitley and sons of Finney Avenue; Mrs. S. M. Ewart, Sedalia, Mo.; Mrs. Nannie Wilburn, Mexico, Mo.; William A. Sublette, Arbuckle, Cal.; Mrs. Mary M. Moore, Georgetown, Ky.; Mrs. E. McCammon, Denver, Cola.; Mrs. Georgia Grennlie, Kirkwood, Ill.; Mrs. Salsie A. Higgins, Crab Orchard, Ky.; James Sublette, Mexico, Mo.; William Sublette, Varsailles, Mo. They are descendants of Pinckney Sublette.

Altogether there are 400 claimants to the land. If time ever comes when the case is finally disposed of, the bones of Pinckney W. Sublette will be buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery beside those of his little niece, Fannie Sublette, whose existence was never even known to him, but whose death a half century ago caused his own bones to be taken from their resting place in a lonely prairie grave and carted a thousand miles to the home of his youth to be wrangled over for years by opposing groups of lawyers.”

Sources:

Amy Keach

Wow! That is a great story!

Mgoddard

Thanks Amy! That means a lot to me 🙂