There may only be a whisper of the Illingworth family name in the Oregon Territory, but a closer examination reveals an impact on early trail expeditions that stretched from Idaho, across Montana, Wyoming, the Dakotas and further to Michigan. The people who envisioned daring expeditions, and who sought to chronicle those efforts, are often the ones who opened the imaginations of those who would follow in the settling of the West.

The Stereoscopic Eye on the Frontier West was originally published by Montana, The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 25, No. 2, Spring, 1975 by Jeffrey P. Grosscup. He was a graduate student at the University of Minnesota School of Journalism, where he specialized in photographic and speech communication. This article was condensed from a paper written as part of the thesis requirement for his M.A. He went on to have a very successful career in photography, influenced in part, I imagine, by the man he had researched.

Photographs depicting life back in 1800’s, of the wagon trains, the ranches, the children, and all those who endeavored to “settle the West” have a particular appeal as visual representation of the lives of our ancestors. They give us a view not always adequately portrayed in the diaries and memoirs that documented their experiences on the Oregon Trail or the hardships they endured in their quest to start a new life in the West.

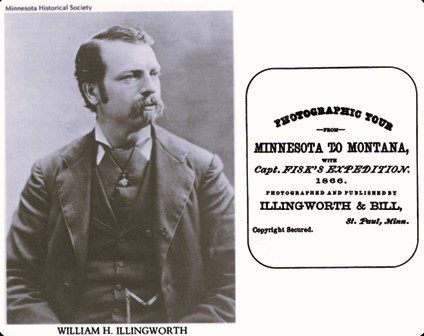

This “visual representation” becomes more poignant after the discovery that the photographers of those early days are a part of my own history. I first wrote about this after discovering that George I. Hazeltine posed on a branch of my family tree and wrote “Imagines of Family Research.” It came to pass that another photographer, William H. Illingworth, also resides in my family tree, as my 3rd great-grandfather of wife of 1st cousin 1x removed. His adventures, as you will read below, led him to document, through his lens, the journeys of James Liberty Fisk who led important expeditions to Montana, and who is my 10th cousin 3x removed. True, the family connections are distant, and not blood relations, but rather, connected through marriages that blended family lines. I relish the stories that arise from those connections.

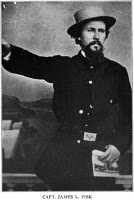

James Liberty Fisk 1835-1902

Here then, is the most remarkable story of a bold, troubled, and talented man who captured unique images from history of the late 1800’s.

THE MODERN WORLD has become so accustomed to the sophisticated and pervasive applications of photography that it is difficult to understand the explosiveness with which it burst upon the American scene in 1839. To the people of the Nineteenth Century, a photograph – and its forerunner, the daguerreotype – was a miraculous thing, an exquisite piece of reality which could preserve forever the faces of loved ones, important events, and fleeting scenes. Instinctively, people realized that a photograph was an historical document which could offer a kind of immortality, and they literally clamored for the photographers’ services. It was this mania for photography – as well as its commercial possibilities – which impelled a young English-born clockmaker named William Henry Illingworth to learn the new craft. This man, whose later life was clouded in anonymity and tragedy, not only learned the basic skills of photography as they were then known, but his adventurous spirit led him westward to document for posterity two vitally important exploratory expeditions.

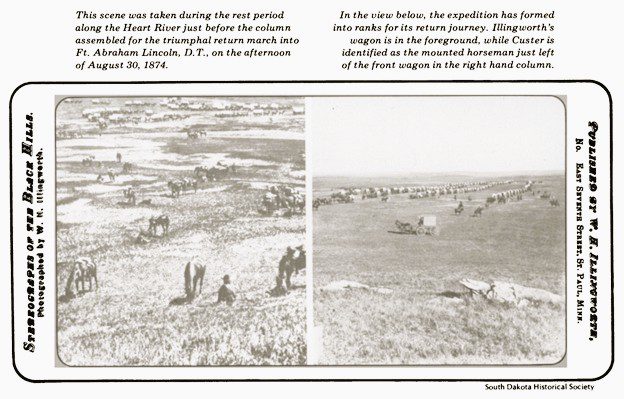

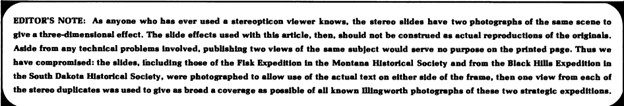

IN 1866, ILLINGWORTH volunteered to join the Fisk Expedition which sought a safe and practical land route from Minnesota to the gold fields of Western Montana. From this, he produced a superb series of views documenting more than two months of covered wagon travel across the plains. Even in his own time, however, he received little credit for his efforts because most of the published views bore the name of another photographer. Eight years later, in 1874, Illingworth was a quasi-official member of the Black Hills Expedition led by George Armstrong Custer. This series is considered to be as fine as any made by his more noted contemporaries who were also photographing the western scene. It is Illingworth’s association with this expedition and its notorious commander which has given him his only footnote in history. Yet at a time when most photographers were reluctant to leave their studios, Illingworth left his home and family to travel the rugged terrain for months at a time by wagon and on horseback with cumbersome equipment and portable darkroom to make the images he wanted.

On September 20, 1842, William H. Illingworth was the son of an English Jeweler and clockmaker who brought his family to this country from Leeds, England, in the 1840’s. The family first settled in Philadelphia, but in 1850 moved west to St. Paul, Minnesota.1 It was his father’s intention that William become a clockmaker, but by the time he neared his twentieth birthday, the young man had already been caught up in the excitement of photography.

In the summer of 1862, William went to Chicago and spent two months learning the new craft, apparently as an apprentice. Chicago was then busily sending troops and supplies to the Civil War, and Illingworth seems to have spent much of his time trying to avoid the Illinois draft, even going so far as to write Governor Alexander Ramsey of Minnesota for exemption from the draft from any state other than Minnesota.2 He was back in St. Paul early in the Fall of 1862, working in his father’s shop while doing a little photography on the side. Illingworth’s technical abilities were apparently better than many other amateurs of the period, and he gradually established a reputation. By 1864 he was listed along with professional photographers in the St. Paul city directory.

On September 26, 1863, Illingworth married Catherine Gunnuh, and a son, William I., was born in 1864. During this period, 1864 to 1866, Illingworth’s studio was in his father’s clock shop on Jackson Street between Fifth and Sixth. Relations between father and son, however, were not always amicable, for at one point the senior Illingworth had to resort to the courts to receive payment for 100 old watches which his son had sold with the alleged intention of pocketing the money.3

Possibly it was the resolution of this suit in 1866 which led William to be caught up by the excitement surrounding the organization of the Fisk Expedition, planned to establish an immigrant route across the northern plains. It is likely, however, that it was the commercial prospects of photographing the expedition which appealed more to Illingworth. The public at the time was quick to recognize the effort that went into scenic photography, and it clamored to buy almost any view on the market. In particular, the demand for views of western scenery was insatiable, and Illingworth saw a possibility for making some money from the venture. Thus, he joined the expedition, not because he was hired to photograph its journey, but because he volunteered on his own

The heroic qualities of his gesture should not, however, be ignored. Fear of hostile Indians surrounded and delayed the expeditions planning and, in fact, Captain James L. Fisk had set out on the venture a year earlier, only to turn back after skirmishes with Indians. Because of this earlier failure, people were fearful of any journey across the Dakota Territory and skeptical of the expedition’s chances for success. Thus, Illingworth’s decision to leave his studio, his wife and infant son, and travel without pay is all the more striking.

In promoting the expedition, Captain Fisk theorized that a permanent and safe overland route from Minnesota to the gold fields of Montana would attract easterners to outfit in Minnesota. As a result of these commercial inducements, Minnesota businessmen strongly supported the venture, hoping that such a route would open new markets for the state’s surplus products. With this support, the expedition was advertised far and wide, and ultimately over 325 people from many states and Canada joined its ranks.

On May 31, 1866, the day of his departure for the expedition’s rendezvous at St. Cloud, Minnesota, the ST. PAUL PRESS noted Illingworth’s understanding under the headline “Photographic Tour from Minnesota to Montana: Messrs. Illingworth and Bill (the former of St. Paul, the latter of Hartford, Conn,) have associated themselves together for the purpose of entering upon a photographic tour from Minnesota to Montana, under the auspices of Captain Fisk’s Expedition. These enterprising young artists have nearly completed their outfit and will be ready to leave this city for St. Cloud by the morning train tomorrow. We understand the intention of the artists to be, to take sketches along the whole length of the northern route, commencing on the frontier of Minnesota and ending at the base of the Rocky Mountains. The pictures of various sizes will embrace the most striking features of landscape scenery to be met with along the river courses, on the billowy plains and among the canyon and coteau [sic] of the country, immediate and beyond the camping ground of… Fisk’s party, will be faithfully portrayed from day to day, while a herd of buffalo feeding on green pasture or lumbering over the prairie will be instantaneously transfixed and taken in a body by the instruments in the hands of these clever young men. If Illingworth and Bill are as successful in getting up their photographic representations as they expect to be on this tour, their pictures will be in large demand, and their labors met with a handsome reward.“

As the PRESS indicated, before leaving with the Fisk party, Illingworth had associated himself with one George Bill [de Bill], a twenty-six-year-old Civil War veteran who had only recently arrived in Minnesota. Although the precise nature of their agreement is not known, it is likely that Bill was to serve as Illingworth’s assistant, for it is unlikely that he contributed any photographic skill. Possibly he viewed this as an opportunity to learn the trade. Nevertheless, following the expedition, Bill gave up photography, married, and settled in St. Cloud, establishing himself as a tinsmith.

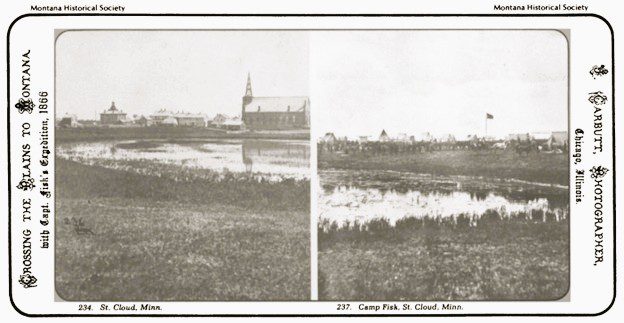

ILLINGWORTH AND BILL arrived in St. Cloud on June 1, 1866, and took their first views of the Fisk camp on June 2 and 3. There they were assigned a wagon on which they loaded Illingworth’s stereoscopic camera and the equipment and chemicals necessary for making wet plates.

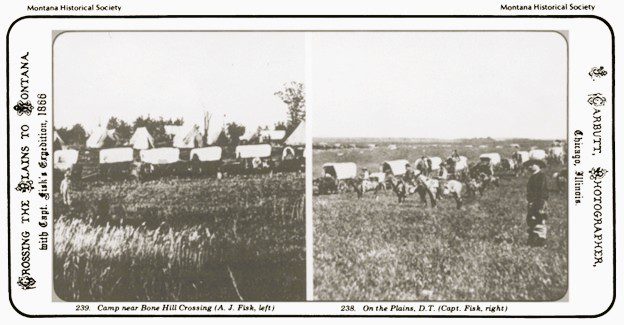

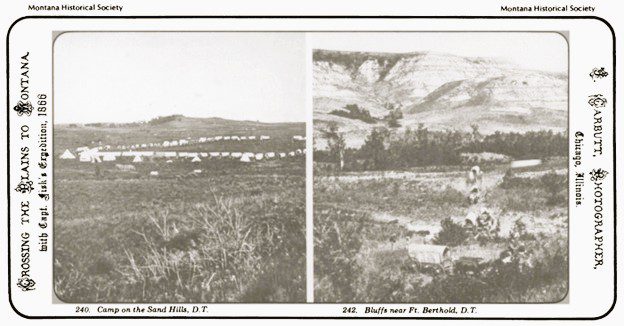

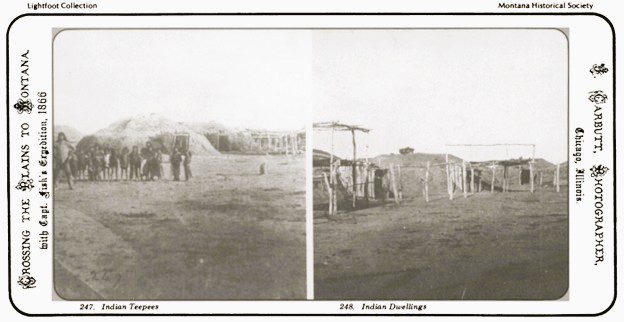

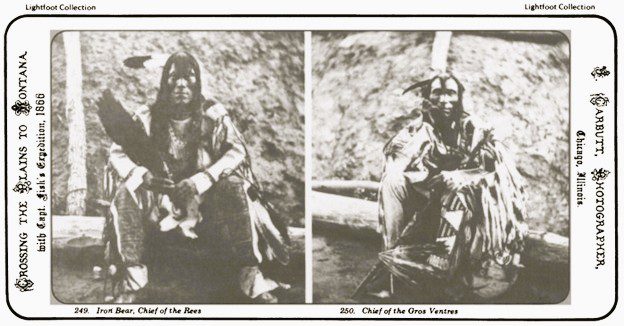

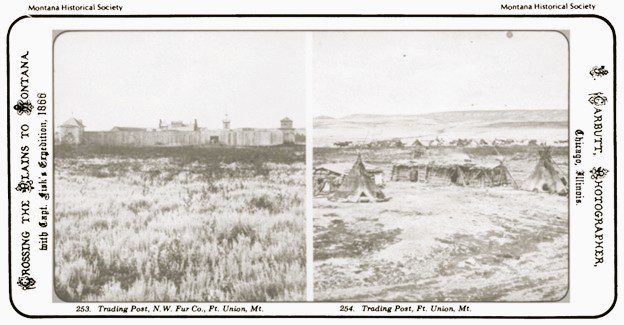

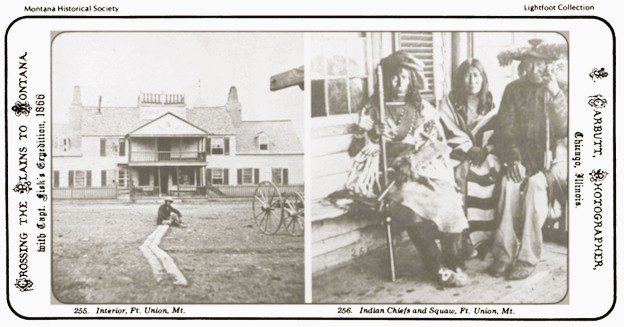

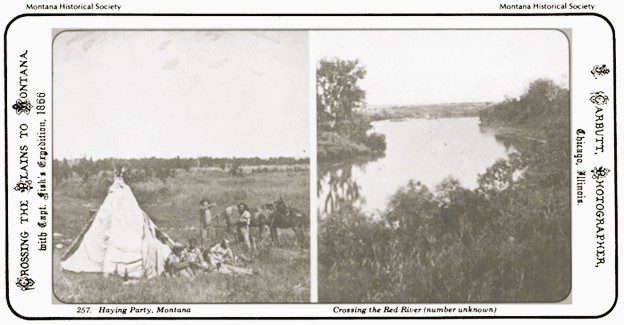

During the two months the photographers traveled with the Fisk party, they produced approximately thirty stereo views. These views, which one photographic historian has called some of the “most successful” of the early western photographs,4 record for future generations the way ox-drawn wagons crossed the plains, made their river crossings, and formed their camps at night. The photographs also show military posts and Indian camps encountered along the route. Only a few are strictly landscape views.

Illingworth’s pictures of Fort Union have special value, for they are the only known photographs of this vitally strategic post at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers which served as the gateway to Montana from the dim early years of the fur trade until its destruction in 1867. Moreover, the views of Indians are significant, for stereo views of Indians taken prior to 1879 are very rare. At least five of the Fisk series are of Indians; two are strong environmental portraits, while others show the Indians in their natural habitat in their camps, and around their dwellings.

The diaries of Wilson B. Harlan, a member of the military security force accompanying the Fisk Expedition, and Andrew J. and Robert E. Fisk, Captain Fisk’s brothers, record the day-to-day hardships the party experienced with drought, torrid heat, mosquitoes, driving winds, drenching rains, as well as with a herd of several thousand stampeding buffalo which narrowly missed the expedition.5

Illingworth and Bill, however, faced even greater difficulties in carrying out their purpose, and it is remarkable that they managed as many as their thirty stereo views. In order to make a single plate they had to coat a glass plate with a wet solution of collodion and potassium iodide, sensitizing it with silver nitrate in a darkroom. Then the plate – which could not be touched with the fingers – was placed in a holder with a removable shield. All this went into the camera, whereupon the shield was removed. The plate, which had to be exposed within a few minutes so as not to lose its sensitivity to light, was exposed by removing the lens cap for a few seconds. The exposed plate was then rushed to the darkroom before the emulsion dried and developed.

This technique, known as the wet plate process, required a great deal of cumbersome equipment, dark room, plates, chemical bottles, tripods, camera, and papers – all of which had to be taken along into the field. Most of all, the process required water, and as the expedition proceeded across the Dakota Territory, the water supply became extremely scarce. When found at all it tended to be muddy or alkaline, conditions which also limited the number of images Illingworth could make.

The water supply was very critical on July 12 and 13, for on neither of these days was any at all found. Camp broke on July 14 before sunrise and the expedition traveled a full day before any more was found. On July 15, wells had to be dug to water the livestock. On none of those days do the diaries make mention, as they usually did, of any photographs being taken.

Moreover, the published version of the Fisk stereographs indicates that no views were taken during the 240 miles between Bear’s Den (July 1) and the area near Fort Berthold (July 19). Although Illingworth and Bill had originally intended to accompany the expedition to its destination – Helena, Montana, at the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains – the two left the expedition on August 3, when it reached Fort Union, just west of the Dakota- Montana border.6

Because of the widespread fear of hostile Indians, it is unlikely that Illingworth and Bill attempted to return to Minnesota on their own. It is more likely that they stayed at Fort Union until a boat could take them down the Missouri to a point where they could pick up a military escort for the overland journey back to St. Paul.

Once back in St. Paul, Illingworth and Bill immediately began work on the publication of the views. Because of their limited financial resources, this series, bearing the Imprint, “Illingworth and Bill, St. Paul, Minnesota,” is very limited and is characterized by hand lettered titles, misspelled words, and amateurish mounting and trimming.7 In addition, Illingworth and Bill published a number of half stereo “cartes de visites” of the expedition views.

Certainly, Illingworth realized that the financial exploitation of his photographs was limited because he lacked the capital to launch a full-scale publication or to properly market his product. Thus, late in 1866 or early 1867, he sold his negatives and the rights to them to John Carbutt, an established Chicago photographer, a noted collector of stereographs, stated that in 30 years of collecting he had only seen six with the Illingworth and Bill imprint. These are currently in his possession. Photographer and publisher Carbutt was in St. Paul not long after Illingworth returned from the Fisk Expedition, photographing the areas of the St. Croix River and Minnehaha Falls. While in St. Paul he learned of Illingworth and Bill, recognized the market for the Fisk Expedition views, and made an offer to purchase out-right title to them. Carbutt had already published several series of western stereo views, including the building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, and an excursion to the 100th Meridian, and he felt the Fisk series could augment them.8

By late spring of 1867 Carbutt had published the Fisk series under numbers 234 to 260 of his own collection. Much more professionally published than was the limited Illingworth series, these views were printed on yellow stereo mounts which credited Carbutt as both publisher and photographer. It was, however, a common practice at the time to dispense with proper credit lines when negatives were bought and sold.

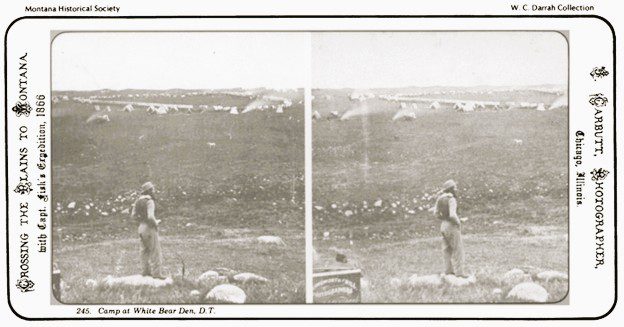

In view of this change of ownership it is interesting to compare Carbutt’s stereo #245, “Camp at White Bear Den,” with Illingworth’s own version. Carbutt was not about to juxtapose the photographic box clearly labeled “Illingworth and Bill” with his own Carbutt Photographer byline. The problem was alleviated by some judicious cropping.

The Philadelphia Photographer made the following comment in its June, 1867, issue about the Carbutt series: “Crossing the Plains to Montana with the Captain Fisk Expedition, 1866- this is a title given to a series of about 30 stereographs sent us by Mr. John Carbutt, of Chicago, from negatives by Messrs. Illingworth and Bill, who accompanied the expedition. They are a most interesting and valuable collection and give one a fine idea of the tediousness, the loneliness, and the danger of a trip across the vast plains of the west. Some of the portraits of Indian chiefs and squaws give one a fair chance to study the character of these horrid creations of red dust. There is but little to love in them we feel assured. Alas, that poor Glover [another photographer killed by the Indians during the previous year] should have fallen into such hands. The pictures are all well taken, considering the difficulties, and only add to our desire to visit that great section of our country with our own camera. The printing and finishing is in Mr. Carbutt’s best style.”

THE FISK EXPEDITION photographs on these pages are perhaps the most comprehensive assemblage of the series published in the past century. No single archive or collector has all the photographs displayed here.9 One collector has several of the original Illingworth mounted stereographs which are not duplicated in any collections of the Carbutt series, suggesting that Illingworth did not sell his entire collection or that Carbutt did not publish all views.

Also included are a number of the “cartes de visites” when they show subject matter different from the existing stereographs.

In examining any stereograph reproduction, one should keep in mind that they were intended to be viewed through a stereoscope. The principle of the stereoscope, which was one of the most popular forms of entertainment during the last century, actually preceded the invention of photography by several years. Overcoming the flat, one-dimensional nature of photography, the stereoscope provided the viewer with an image magically seen in three dimensions. This phenomenon is explained by the fact that the two human eyes see an image from two slightly different perspectives.

The stereoscope camera with its two lenses 2-1 /2 inches apart simulates this. When viewed through the stereoscope, the images produced by the two lenses come together to give the illusion of depth. Thus, the large, flat foreground of Illingworth’s stereographs which seems to indicate poor composition, when viewed through the stereoscope, becomes an intrinsic part of the picture. For example, the man in #245 stands not on the vast level plain as it appears to the naked eye, but at the top of an elevation overlooking the wagon camp below.

BEGINNING IN 1867 and for the next seven years, William Illingworth located his studio at four or five different addresses on the near east side of St. Paul. During this time, he became quite prolific as a publisher of stereo views, the majority under the title of “Stereographs of Minnesota Scenery.” There are several hundred – perhaps as many as a thousand – different views in this series. Most of the stereo mounts state that Illingworth was also the publisher, but a good number bear the names of Burritt and Pease (1868- 1871) and Huntington and Winne (1872-1875).

During his early years as a photographer, Illingworth relied on Burritt and Pease to publish his views, which did not require an investment in equipment and supplies and allowed Illingworth to devote himself to making views. When they left town, Illingworth began to publish some of his own while relying on Huntington and Winne for some selective publishing until 1875.

These views, most of the original glass negatives of which are now at the Minnesota Historical Society and the Minneapolis Public Library, are not indexed according to photographer and are therefore difficult to identify. Like most early photographers, Illingworth scratched or painted numbers on his glass negatives which aids identification. Unfortunately for research on his work, however, Illingworth’s system is inconsistent and confusing, and breaks down at several points. Although most of the views are landscapes, a good percentage show buildings, modes of transportation, and, most importantly, the ordinary aspects of life in the Nineteenth Century.

Illingworth’s rising professional fortunes were shadowed during this period by personal problems and uncommonly bad luck in marriage. His first wife died in about 1867. Illingworth married a second time in 1869, but she also died within four years. On April 8, 1872, he married his third wife, Flora Leonard. At first their marriage was a happy one – he named several of his Black Hills views Floral Park and Floral Valley in her honor – but in later years it became increasingly rancorous. In addition to his son, William, Illingworth was also at some time responsible for another child, John Illingworth (John H. Cheever).10

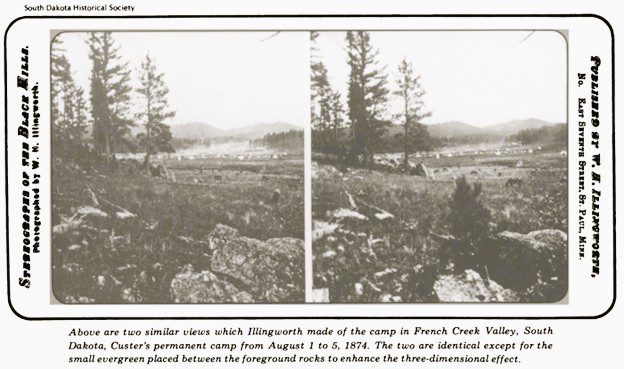

Photography, however, clearly gave Illingworth a great deal of pleasure and his work reflects an increasing technical ability and artistic sensitivity. Through practice, he learned how to dramatize his stereograph composition through the interplay of texture and space for optimum effect, and his views became increasingly graceful and balanced. Illingworth was particularly adept at enhancing the three-dimensional effect of his views by composing them with a prominent object in the foreground. One photograph of his two sisters which contains two exposures of one of the sisters, reveals that Illingworth had indeed mastered the technical problems of photography.11

Two photographs of Illingworth himself show that he was an avid hunter and outdoorsman. One is a studio portrait showing four ducks and a goose strapped to his belt. The other shows him with a hunting and fishing party on the St. Croix River. No doubt his landscape photography provided Illingworth with a welcome opportunity to work outdoors while traveling widely in Minnesota.

By 1873, ILLINGWORTH was at the peak of his career. The country, however, was in the midst of a severe economic depression, a financial slump that prompted a number of photographers to leave their studios for the financial lure that photographing the west presented. Illingworth’s restlessness, his love of the outdoors, his sense of excitement and adventure, as well as the economic pinch, led him to his association with the controversial Black Hills Expedition led by George Armstrong Custer in 1874. Plans for this expedition aroused much interest. In the eyes of the army its purpose was to reconnoiter an unknown patch of the west known as the Black Hills for a possible military fort because hostile bands of Sioux were seeking refuge there after raids in Nebraska. To others who were restless to push westward, the purpose was to look for gold. The discovery of gold – even on lands legally held by the Indians – could be expected to relieve some of the pressures of the economic panic, and gold-hungry men along the frontier were ready to violate treaties and risk an Indian uprising by moving into the area if Custer found gold.

Several years earlier a group of miners called the Black Hills Exploring and Mining Association began promoting an expedition to the gold fields, but the army refused to provide protection or allow it to begin. In 1867 another private group numbering some 300 gold seekers had to be halted by army intervention.

For some time thereafter the army remained steadfast in its determination to keep white men out of the hills, in order not to risk another Indian war. By 1874, however, the combination of mounting public pressure to find gold, the national economic situation, and the concern over Indian use of the area prompted the army to authorize an expedition by the Seventh Cavalry. Although emphasizing officially that the expedition was to perform reconnaissance, not to prospect for gold, two civilian miners and a geologist were permitted to accompany the column.

How Illingworth became involved with the venture is not entirely clear. Although it is possible that he sought out the expedition’s officers, it is more likely, because of his reputation from the Fisk Expedition, Colonel William Ludlow, the engineering officer assigned to the party, sought him out.

Their agreement that the army would carry Illingworth on the rolls as a teamster so that he could draw a salary suggests that the army had indeed desired his presence, for many expeditionary photographers were paid only subsistence, their main income being derived from the sale of stereographs.

The military provided Illingworth with all the necessary equipment and material, as well as a horse, forage and rations. Moreover, he was assigned an assistant and the same photographer’s wagon used by Stanley J. Morrow, another early photographer, during the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873. In addition, Illingworth received some miscellaneous articles valued at $46.00.

In return for all this, Illingworth was to supply Ludlow with six complete sets of his photographs, but Illingworth was to retain undisputed possession of the negatives when the pictures were delivered.12

THE BLACK HILLS Expedition, said to be the best ever fitted out for the plains, rendezvoused at Fort Lincoln, near present-day Bismarck. Even a military band, something new in western plains travel, was included in the retinue. General Custer, commander of the expedition, said that the size of the party was meant to prevent trouble, not to make it. There were indeed rumors, as the column set out, that Sitting Bull and his followers were about seventy miles to the south with plans to intercept the column and contest every foot of its journey. This did not materialize and the few Indians the expedition encountered were generally startled by its sudden and unexpected appearance.

Illingworth traveled to Bismarck on the Northern Pacific Railroad, taking views of the towns passed enroute. These subjects, which include views of Fargo and Bismarck, are included in his stereographs of Minnesota series, not in the Black Hills series.

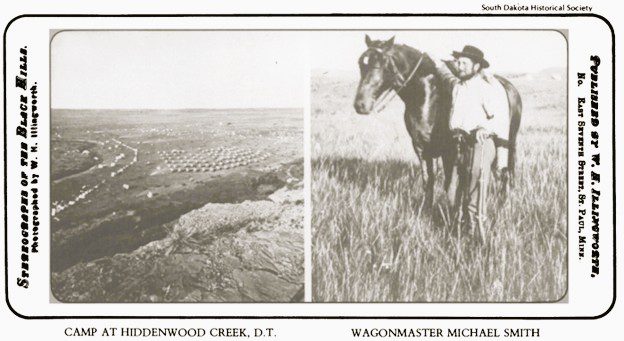

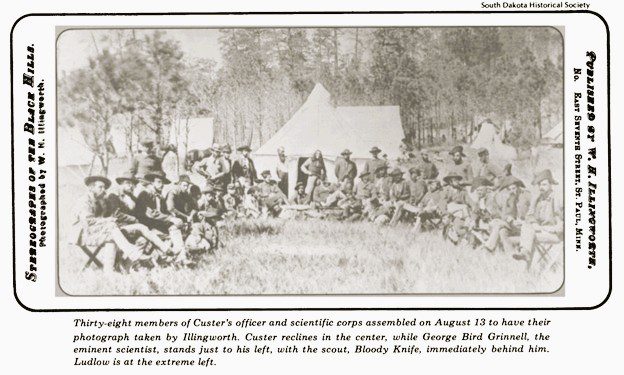

From July 2 to August 30, Illingworth traveled over 883 miles with the force, photographing campsites, significant terrain, the expedition’s officers and scientists, and the wagon train on the move. During this period, he made approximately seventy-three separate views, although a number are duplicate views with the camera position changed slightly. The total number of views finally published in the Black Hills series, however, numbered only fifty-five.

Illingworth’s were the first photographs ever taken of the Black Hills, and apart from any specifics that may have been directed by his client, Colonel Ludlow, he intended to take views that would show an eager public what the area looked like. Ludlow also wanted views which would serve as reference points for his official report, not so much to document the journey, but rather to show what the expedition went to see. Thus, in only two of the views Illingworth portrayed close-ups of the officers and scientists, and none of the photographs provide a candid look at camp life.

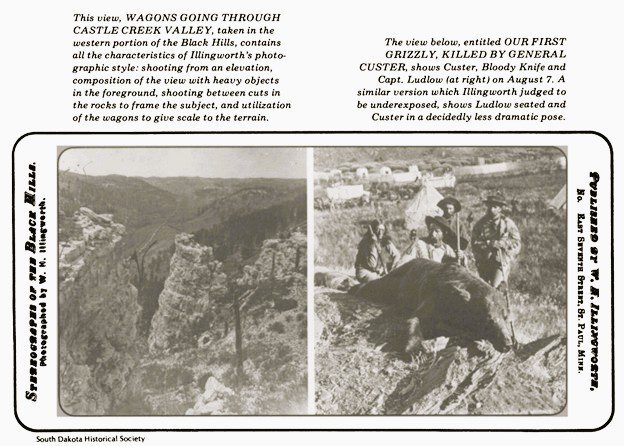

With the exception of a few views, Illingworth generally carried his heavy camera and portable darkroom up the sides of the rugged hills in order to attain the vantage point he wanted for his shot. One of the most dramatic views shows the expedition as it traveled through Castle Creek Valley at the north entrance to the Black Hills.

So impressed was this author with the sense of scale and elevation created by this stereograph that Illingworth’s foot- steps were followed.

The vegetation in the area is certainly heavier today than it was a century ago, but it was not so thick that a nearly straight route to the summit could not be followed. The hill has a 30 to 40 percent grade and near the top there is considerable loose rock which makes footing difficult. Carrying only a fifteen-pound camera and a small tripod, this writer reached the summit in twelve minutes, much exhausted after a brisk walk. It then required another twenty-five minutes to find the exact location from which he sighted through a cut in the rocks, the wagon train in the valley below.

It seems unlikely that Illingworth could have loaded his camera while on the valley floor, raced up the hill, decided on his location, set up his camera, composed the image, exposed it, made the six-minute run down the hill to his wagon and still had a plate to develop that was wet. A more likely alternative is that he took a portable darkroom with him up the hill. To do so Illingworth, with all of his heavy equipment, had to be traveling at least an hour ahead of the main body of the expedition to have ample time to set up before the wagons passed. Illingworth made at least two separate negatives of this view, which suggests even more strongly the presence of a portable darkroom at the camera position.

Illingworth was not as selective in his photographs of the Black Hills as he had been on the Fisk Expedition. Because Ludlow may have instructed him to make some of the views, a high percentage are strictly landscape panoramas, lacking variety. Although Illingworth did a good job in relating much of the terrain to the expedition’s route by showing wagons and tents in the distance, many more of the images need this relationship to give them much significance.

Nevertheless, there are many interesting examples of Illingworth’s sense of image composition and framing in the Black Hills series. As in the Castle Creek Valley view, many of his images were taken from lofty elevations, and the exposures were frequently made through a “V” between rocks. One view clearly indicates that Illingworth rather hurriedly placed a small evergreen by some rocks in order to make the foreground more prominent. There is a similar view, identical except for the absence of the tree. The much published photograph of Custer and the grizzly bear actually is one of two photographs of the same subject. Deciding that his first attempt was underexposed, Illingworth repositioned two of the men and increased the exposure.

An examination of the original negatives now at the South Dakota Historical Society suggests that Illingworth’s equipment on this expedition included a stereographic camera with interchangeable lenses for making single, non-stereographic images. About six of the views were made as single panoramas. Identical stereo negatives of the same scenes, taken from identical positions, suggest that he had merely changed lenses for his second shot.

In 1874, just as he had in 1866, Illingworth did not make any paper prints in the field but stored his negatives in a wooden box especially made for field work.

ONCE BACK IN St. Paul, Illingworth became embroiled in a legal dispute with the army over his photography. Despite the agreement with Ludlow to furnish six sets of prints, Illingworth delivered Just one incomplete set. When Ludlow complained, the photographer said he did not have the means to do so. Ludlow, however, had evidence that Illingworth was already selling completed sets commercially through Huntington and Winne. The colonel then took Illingworth to court on charges of embezzling government property. The case was dismissed on a technicality in 1875; the court ruled that the glass used was the property of the photographer.13

It seems strange that Illingworth would be willing to be taken to court rather than produce five more sets of prints. However, evidence suggests that the negatives were not accessible to him because they were in the possession of Huntington and Winne. A newspaper account printed before the expedition stated that the photographs were to be taken by Huntington and Company. This suggests that Illingworth had a prior arrangement with them that he was forced to honor. After Huntington closed his business in the latter part of 1875, Illingworth published the views himself.

Publishing this series of views occupied Illingworth’s time for many months. Like other small publishers of stereo views who did so in addition to their regular studio business, he could not produce more than two hundred cards or about four complete sets of the Black Hills series in a week.

Busy with this work, Illingworth was artistically and financially at the peak of his career, but from this point his work declined sharply. Stereo photography began to decline in popularity in 1878 while at the same time, small publishers such as Illingworth were gradually driven out of business by the competition of larger firms who had more efficient production methods and better marketing techniques.

This decline in the popularity of stereo photography forced Illingworth to rely more and more on his portrait studio. At the same time further personal problems spurred his professional decline. On March 5, 1888, the St. Paul District Court granted a divorce to Flora Illingworth: The defendant W. H. Illingworth has been guilty of cruel and inhuman treatment of the plaintiff as charged against him in the complaint herein, and further that said defendant … for the space of more than one year immediately preceding the filing of the complaint in this case was a habitual drunkard and guilty of habitual drunkenness during this time.

Witnesses supporting Mrs. Illingworth said that her husband was often intoxicated. One said he had witnessed the photographer drunk as many as three dozen times during an 18-month period. Mrs. Illingworth stated in court that during the last year she lived with her husband, “he would get drunk and remain so, two, three, and even five days at a time, always until drinking made him sick then perhaps he would remain straight for perhaps two weeks.” Other testimony indicated that during these periods of intoxication, Illingworth would go into fits of anger, frequently striking his wife.14

In his defense, Illingworth could only make the allegation that he had drunk beer daily since he was five years old and that he was in the habit of drinking only two or three glasses of beer daily, not the twelve charged by his wife. Although there is no other evidence to indicate Illingworth’s alcoholism, it is likely that their relationship was worse, not better, than indicated by the court brief. Divorce was a most unusual occurrence at the time, and the associated stigma would have made women hesitant to resort to it unless the situation was intolerable.

FOLLOWING THE divorce, Illingworth went downhill rapidly. Continuing to drink heavily, he was forced to dispose of most of his photographic equipment and household Items in order to support his habit. Finally, in 1893, at the age of 50, Illingworth, sick, impoverished, and depressed, ended his own life with a shotgun blast to the head.15

In spite of his destitution, it is important to note that William Illingworth maintained a pride in his photography, and he refused to sell his collection of over 1,600 negatives. In 1900, his son, William, sold the collection to Edward A. Bromley, a Minnesota journalist and photographer. Bromley’s total collection consisted of over 7,000 negatives and prints, representing the work of thirty photographers. In 1914, because of falling health, Bromley began disposing of his collection, wisely concerned that it go to public organizations which would preserve it for future generations.16

The first segment of the collection was sold to the Minneapolis Public Library in June 1914, for a sum of $575.00. This collection of 1800 items consisted of a representative sampling of his entire collection and included a number of Illingworth negatives. In 1920, Bromley sold the Black Hills negatives, with the exception of one half of a stereo negative that had been cut, to the South Dakota Historical Society for $60.00. After his death the remainder of Bromley’s collection was sold to the Minnesota Historical Society for $1,000.00.17

In subsequent years, Illingworth photographs have found their way into numerous books and periodicals. Most widely published have been those of the Black Hills Expedition, primarily because of the long national interest in General Custer. Yet Illingworth himself remains lost in obscurity. As an individual who witnessed significant developments in the growth of the west, Illingworth was both a sensitive artist and perceptive historian, recording the past with the absolute truthfulness of the camera’s lens. In death a pauper, William Illingworth left posterity a rich legacy.

Notes & Citations:

1. Record of birth, Leeds Registration District, Leeds, England; Newsome, Pen Pictures of St. Paul, Minn., and Biographical Sketches of Old Settlers.

2. “Letters Received, Draft and Local Conditions.” Minn. Hist. Soc., Box 10a, fr. 152-3.

3. Ramsey County Marriage Records, St. Paul; Record of Oakland Cemetery, St. Paul; Minnesota Supreme Court Record, 1865-86, Illingworth vs. Green- leaf.

4. Taft, Robert, Photography and the American Scene. N.Y., Dover, 1964, p. 276.

5. The Fisk diaries are part of the Fisk Family Papers at the Montana Historical Society; the Wilson B. Harlan diary is owned by G. D. Harlan. Inglewood, Calif., a grandson of Wilson Harlan.

6. Harlan diary, p. 155.

7. Letter of William C. Darrah, Gettysburg, Pa., to the author.

8. The final disposition of the Fisk Expedition negatives is unknown. Possibly they were destroyed in the Chicago fire of 1871. Carbutt sold his gallery in 1870, but it is not known if the negatives were sold with the building which burned in the fire. Carbutt moved to Philadelphia in 1871 to work on the Woodbury process of photo duplication.

9. In addition to Darrah’s holdings and several other small holdings, the Montana Historical Society has fifteen original Carbutt stereographs and Frederick Lightfoot of Huntington Station, N.Y., has a nearly complete set of the original series. Since the author’s research he has sold this series.

10. The identity of Cheever is problematic. Although his relation to Illingworth cannot be established, he is listed in the St. Paul probate court records along with William J. Illingworth as next of kin to the photographer.

11. This photograph is in the possession of Mrs. H. E. Olson. St. Paul, Illingworth’s niece.

12. Ludlow to Chief of Engineers, Jan. 12, 1875, RG 77, National Archives.

13. Ibid.

14. Ramsey County District Court file #27029. Flora A. Illingworth vs. William Henry Illingworth.

15. St. Paul Probate Court file #6747 itemizes the extent of Illingworth’s worldly goods at the time of his death. In addition to his dwelling and the negatives, his estate totaled only $128.00.

16. Bromley to Minneapolis Library Board, June 6, 1914, Minn. Hist. Soc. Coll., Mpls. Public Library.

17. Ibid.; Picture Dept. Bromley Correspondence, 1926, Box 178, Minn. Hist. Soc.; Bromley to Doane Robinson, Sept. 6, 1920, Mss. Coll., S.D. Hist. Soc.

For further research:

Montana Historical Society – Montana The Magazine of Western History

Jeffery Kraus Antique Photographics – Searchable database of photographs

South Dakota Public Broadcasting

Original Citation: Jeffrey P. Grosscup. (1975). Stereoscopic Eye on the Frontier West. Montana: The Magazine of Western History, 25(2), 36–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4517978