As I wrote in “Images of Family Research,” I’ve not encountered many people who aren’t intrigued, and often captivated, by images of family taken in the mid to late 1800’s. These glimpses of family provide an empathetic moment where we briefly experience an instant of their perspective, to momentarily place ourselves in their position, to imagine what their lives may have been like. These old photographs assist us in recovering history of the American West, as well as our own family history.

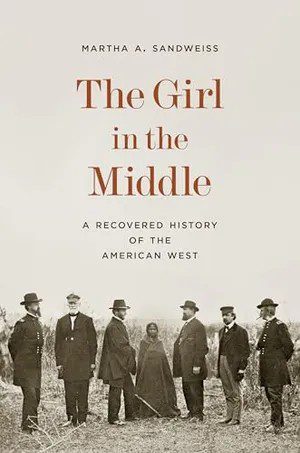

Martha A. Sandweiss is an emeritus historian at Princeton University, with particular interests in the history of the American West, visual culture, and public history. She is the author or editor of numerous books on American history and photography. Her latest book, “The Girl in the Middle: A Recovered History of the American West“, published by Princeton University Press, was recently featured in a Smithsonian Magazine article1.

When Sandweiss saw the photograph, taken by Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner, she wondered, as I often have while looking at these old photographs, “What is the story here?” All the men in the photograph were identified, but not the lone child standing between them. And so, her research began, resulting in a remarkable book. She not only found the name of the girl in the middle, but she also shows how the American nation grappled with what kind of country it would be as it expanded westward in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Many of the stories I’ve written began in the same way… the discovery of an old photograph, and then a yearning to know who the person was and what their life had been like. In the discovery of their lives, we also discover the history of their times and often how they, in turn, impacted history. And then we see that history leading to us, and how our lives were shaped by that past.

Martha Sandweiss was kind enough to allow me to share her story here, as presented in the Smithsonian Magazine article.1 The embedded links take you on a deeper dive of her research and the history of the American West. And she poignantly connects that history to current events and the assault on historical records.

When a Historian Saw This Haunting Photograph of a Nameless Native Girl, She Decided She Had to Identify Her

In 1868, Sophie Mousseau was photographed at Fort Laramie alongside six white Army officers. But her identity—and her life story—remained unknown for more than a century

Sophie Mousseau is identified simply as “Arapaho” on one version of the photo and “Dakota” on another.

And so we pick up Martha’s story…

“As a scholar of 19th-century American photography, I’ve looked at countless old photographs: the carefully labeled portraits of the powerful (always the most likely to be photographed) and the many pictures of women and children, enslaved workers and Native families, rural laborers and urban bystanders that include no identifications at all.

Some years ago, I began to wonder whether I could identify some of the unnamed people in old photographs. Might I be able to name that gold miner, that railroad worker, that soldier lying dead on the battlefield at Antietam? Would my understanding of history shift if I knew who these people were?

My attention focused on a photograph by the celebrated Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner. Taken at Fort Laramie, in what is now Wyoming, in spring 1868, it depicts six white men standing in an oddly formal arc around a young Native girl. The men, all fresh from Civil War duty, are members of a federal peace commission sent west to this fort along the Oregon Trail to persuade the Lakota to move to a newly created reservation.

The handwritten labels on the extant copies of the photograph carefully identify these men: General Alfred Howe Terry, General William S. Harney, General William Tecumseh Sherman, General John B. Sanborn, Colonel Samuel F. Tappan and General Christopher C. Augur. The girl is never named. She is simply “Arapaho” on one version of the photo, “Dakota” on another. She looks straight at the camera and begs us to stare back.

Who is she?

Spinning a spellbinding historical tale from a single enigmatic image, “The Girl in the Middle” reveals how the American nation grappled with what kind of country it would be as it expanded westward in the aftermath of the Civil War.

I looked for her in other pictures made at the fort. She’s not there. I searched through the personal papers of the commissioners and the government records of the treaty negotiations. Nothing. Finally, in the archives of the Fort Laramie National Historic Site, I found a small notecard left by a visitor in 1978. He’d seen a copy of the photograph on display; the blanket-wrapped girl was his grandmother, Sophie Mousseau (link to article by Jessica Mousseau’s website). The name connects an unidentified child to the historical records; it lets us find her story.

Sophie proves easier to track than most girls born on the Northern Plains during the years of the Indian Wars. Traces of her Oglala Lakota mother survive in the spare federal records that track reservation residents. Curious writers recorded her French Canadian father’s memories of the “old days.” Since Sophie’s father turned litigious, and her first husband became a murderer, bureaucratic records also preserve imprints of her life, even as descendants’ memories grow increasingly faint.

Sophie’s life leads us into a sprawling Western world. Born in the Dakota Territory shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War, she died on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, one of the very poorest parts of a Great Depression-riddled nation, in 1936. Her first husband, a white Civil War veteran, effectively kidnapped their five children after he fell in love with another woman. He married her and banished Sophie to the newly created Great Sioux Reservation.

Sophie was working as a laundress at a federal boarding school in Pine Ridge when federal troops massacred some 250 Native people at nearby Wounded Knee in 1890. She later married a mixed-race Lakota who gave up his career as a circus juggler to become a much-valued translator for some of the country’s leading anthropologists. With him, Sophie had another eight children, for a total of 13.

Sophie experienced domestic violence, observed the consequences of military violence, and saw firsthand the consequences of the political and legal violence that denied rights to people like her.

Indeed, she was born of violence. Thirteen years before the photograph was made, Harney, the general who stands with Sophie in the photograph, attacked a Lakota village at a place called Blue Water Creek in western Nebraska. His men wounded a young mother named Yellow Woman and used her infant for target practice. Then they rounded her up and marched her to Fort Laramie. At the same time, Harney ordered all the traders in the area into the fort. There, Yellow Woman met the trader Magloire Alexis Mousseau, who later went by the name M.A. They married, became Sophie’s parents and stayed married for over half a century. The general was an accidental matchmaker.

When Sophie’s parents ushered her into Gardner’s photograph, they saw two men they knew: Harney, whom they’d met more than a decade earlier, and Sanborn, whom they’d just hired as their attorney. Sophie and her family had their place in a West that was both a big place and a small world.

Neither the photographer nor government officials saw fit to record Sophie’s name 157 years ago. But Sophie’s name transforms a banal photograph into a picture that leads us into a world of families and the complicated racial politics of the 19th-century West. Her story transforms a picture ostensibly about men negotiating a peace treaty into a meditation on the endemic violence that shaped so many American lives. When we know who Sophie is, the photograph becomes a different kind of evidence altogether.

Names tether people to historical records. Names are what let us trace people through old newspapers and books, census records and legal documents, family memories, and community gossip. Names are what transform the anonymous people in old photographs into particular individuals with complicated stories of their own.

In recent weeks, as part of a broader assault on historical records, exhibitions and books, government functionaries have scrubbed countless government websites of historical names: civil rights activist Medgar Evers, Medal of Honor recipient Charles C. Rogers and baseball star Jackie Robinson, among others. Amid fierce public pushback, some of the sites have now been restored. Critics insisted those names mattered, not only because they honor individual accomplishments, but because they denote bigger stories about combating racial segregation or fighting for civil rights. Individual stories make the abstract more concrete, the past more complex.

When Ira Hayes, the Pima Indian present in the famous image of the flag raising at Iwo Jima, loses his clear tribal affiliation in an article headline, we lose something. It’s no accident that most of the names and stories scrubbed from the record are those of people of color.

American history needs more names, not fewer. It needs the names of the famous and the names of those who, like Sophie, have remained unidentified in personal and institutional archives. Take that shoe box out of your closet and label your family photos. Everyone’s story matters.”

This article was written for Zócalo Public Square and published in Smithsonian Magazine

Martha’s book is available through Amazon in my bookstore by clicking HERE.

Sources:

1“When a Historian Saw This Haunting Photograph of a Nameless Native Girl, She Decided She Had to Identify Her“, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-a-historian-saw-this-haunting-photograph-of-a-nameless-native-girl-she-decided-she-had-to-identify-her-180986496/

2Sandweiss, Martha. “The Girl in the Middle: A Recovered History of the American West” Princeton University Press, 2025