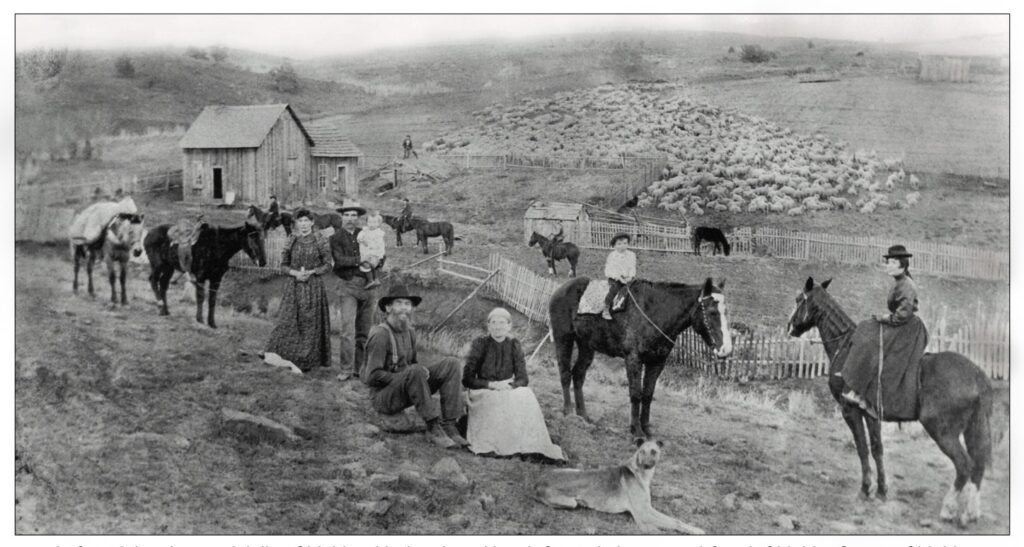

Two Families, One Common Ancestor, Two Hundred Miles Apart tells the story of two Shields families, one in the Imnaha of NE Oregon, the other two hundred miles away in Long Creek, Grant Co. Oregon. What evolves in the story is the discovery that they shared a common ancestor. Separated by miles, they may not have known each other. Their respective circles of family and acquaintances, however, overlapped with many of the same events of early Pacific Northwest history.

As early settlers of Oregon they endured the hardships of settling raw land, they built communities and commerce, they defined culture and law. Too often the backdrop to all this included the displacement of Native American peoples, including Native communities, commerce, culture, and law. Camp Logan – The Fears & Sadness of Settlement describes some of those conflicts from the vantage point of those early settlers. Few were the people who sought to present the Native perspective of this invasion.

From the story of unexpected family connections between the Shields of Long Creek and the Shields of the Imnaha arose another family connection, and consequently, one of the strongest voices for the plight of Native Americans.

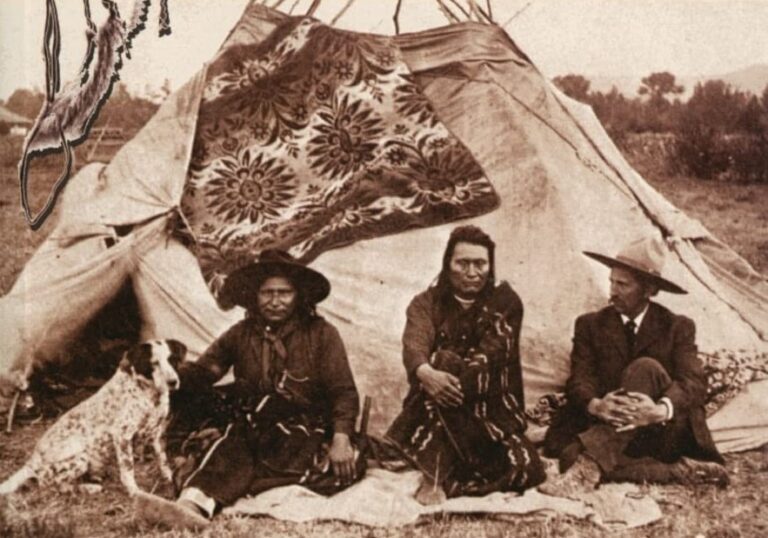

Seated next to James Shields in the photo above is Sarah Amanda McWhorter, 1839 -1923. Just as she was separated from the Shields family of the Imnaha 200 miles to the east, there was another family member she may not have been aware of, for 200 miles to the north, Lucullus Virgil McWhorter, had come from Virgina in 1903 and settled in the Yakima Valley. In 1903, Sarah lived in Warm Springs, Oregon, the future site of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, while Lucullus bought land near what would become the Yakima Indian Reservation.

Biography/History (1)

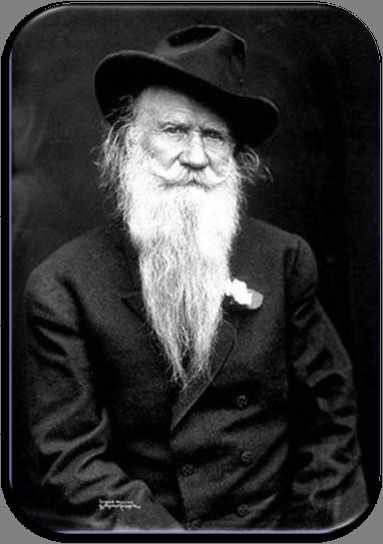

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter was born on the upper waters of the Monongahela River in Harrison County Virginia (later West Virginia) on January 29, 1860. He was one of twelve children born to the Reverend John Minion McWhorter and Rosetta Marple McWhorter, both native Virginians. McWhorter’s youthful orientation to life on the land mirrored his rejection of formal education. Summarizing his formal schooling in a biographical questionnaire, McWhorter observed that he did “Four months annual winter terms [roughly the 3rd grade] of indifferent instruction, during years of minority only.”

He was a voracious if highly focused reader, then and throughout his life. His interest in regional history, folklore, and archaeology originated with youthful forays into the woods and countryside of West Virginia where he hunted for archaeological remains of Indians and early settlers. McWhorter’s critical study of 19th century American history and his romantic appreciation of nature combined to form his view that the American Indian was the true “aboriginal American”.

During his life, he became an ardent ally and supporter of various Indian tribes, strongly sympathizing with their resentment over the often-bad treatment meted out to them by early white settlers and later by the military, “Indian grafters,” and the Federal bureaucracy. In his teens his father took him into the family livestock business (breeding devon cattle) in Berlin, West Virginia. Acting on the impulse for adventure and to see Indians first-hand, McWhorter set out on a lark in 1881 to trek through the coastal regions of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas. Eventually, he saw his first Indians in Oklahoma, where he nearly encountered Chief Joseph and the exiled Nez Perce.

In 1883 he returned to cattle ranching in Berlin, West Virginia, and married Ardelia Adaline Swisher on March 17th of that year. She and McWhorter had three children: Ovid Tullius (b. 1884); Iris Oresta (b. 1886); and Virgil Oneco (b. 1888). Their marriage was tragically cut short when Ardelia died in December of 1893.

During the 1890s McWhorter actively maintained his interest in archaeology and Indian affairs while he continued his work as a cattle rancher. On June 22, 1895, he married C. Annie Bowman. For the next two years the McWhorter family lived in Upshur County, West Virginia, before moving to Darke County, Ohio, in 1897. McWhorter’s dream of settling near Native Americans never wavered. After selling off what he could of disposable property, he and his family left Ohio, moving to the Yakima River Valley in Washington state in 1903. It was there that his involvement with Indian history and culture matured and continued throughout the remainder of his life.

In Washington state McWhorter continued ranching and building his archive of material relating to the conflicts between the Federal government and the Nez Perce and Yakama tribes. (On June 9, 1909, McWhorter became an adopted member of the Yakima Nation. His Indian moniker “Big Foot” attested to the high esteem and affection in which he was held by his Indian friends and associates.)

At the same time, he gathered material relating to Indian culture and the legal status of various tribes after the conclusion of the Indian wars in the 1870s. In 1914 McWhorter met author Cristal McLeod, or Mourning Dove, a Colville (Washington) woman of mixed Indian-white descent who had worked up a draft of a semi-autobiographical novel called Co-ge-we-a, The Half Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range. In a collaborative effort, McWhorter and McLeod devoted much time and expense on finally getting Cogewea published in 1927.

Prior to this, McWhorter had completed work on a historical manuscript dealing with the settlement of the western region of Virginia. This title, The Border Settlers of Northwestern Virginia from 1768 to 1795, was published in 1915. In 1917 his research on the Yakima uprising of 1855 resulted in the publication of The Tragedy of the Wahk-Shum: Prelude to the Yakima Indian War, 1855-1856. McWhorter also worked to advance and secure Indian rights locally and nationally during this time, but the Washington years were especially important in terms of his labors as an amateur historian, linguist, and anthropologist (he was a member of various historical organizations, including the Washington State Historical Society).

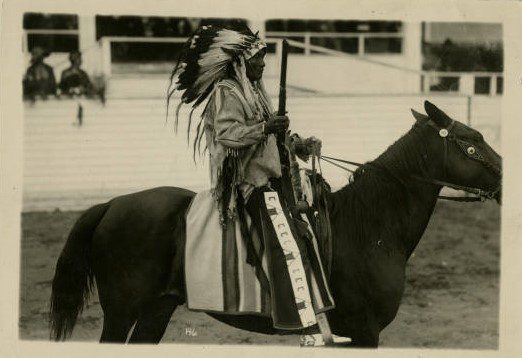

Purely by chance, a fateful meeting with prominent Nez Perce War veteran Yellow Wolf in October of 1907 helped McWhorter in his future investigation of the 1877 Nez Perce War and the Nez Perce generally. (Yellow Wolf needed temporary boarding for his horse, and McWhorter courteously obliged!) In the course of compiling material for this posthumously published “Field History” McWhorter worked diligently to acquire and appraise primary and secondary sources. He recorded first-hand Indian oral testimony, maintained an extensive correspondence, and made direct assessments of battle-sites in an effort to establish an accurate and comprehensive account of the 1877 conflict between the Nez Perce and the Federal government.

Significantly, his research also included interviews with survivors from the armies of generals Howard, Sturgis, Gibbon, and Miles. McWhorter’s historical efforts had the signal value of providing a fresh version of those events based on primary source materials; his books supplemented, supported, or contradicted previously published accounts and interpretations of the same events.

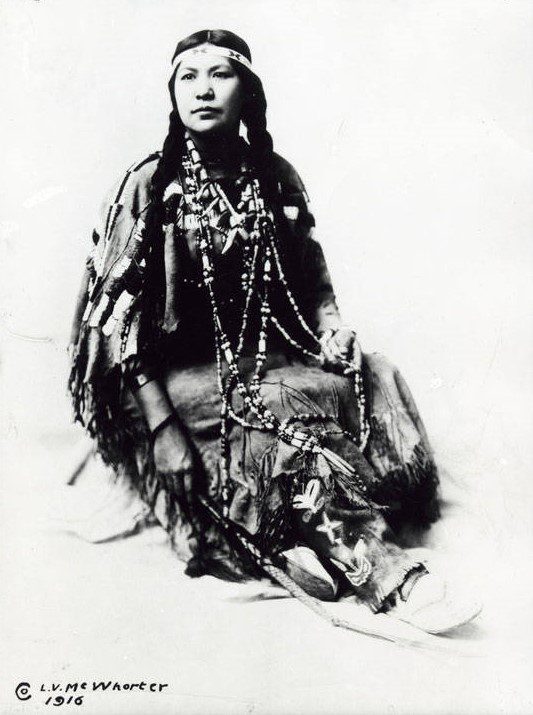

Working with Yellow Wolf, and by utilizing the extensive mass of material (including photographs) he had gathered during years of research, McWhorter published Yellow Wolf: His Own Story in 1940. After his death in 1944, Mrs. Ruth Bordin and Professor Herman Deutsch edited and completed McWhorter’s larger account of the 1877 Nez Perce War. The manuscript material known as the “Field History” was first published as Hear Me, My Chiefs! in 1952. Lucullus Virgil McWhorter died at the age of 84 in Prosser (North Yakima), Washington, on October 10, 1944.

He reflected on his dual role as an advocate and amateur historian of the American Indian in a June 2, 1941 letter to former State College of Washington President E.O. Holland. On being notified that officials at the College had voted to confer on him a Certificate of Merit for his contributions to agriculture and rural life, McWhorter observed that he possessed “No scholastic attainments whatever. My trail just that of a wild, rough and ready field delver. My activity in the Indian domain has [sic] not elevated me in the estimation of the local populace in general.”

The book, Yellow Wolf – His Own Story has had its place on my shelf of Indian history books for nearly 30 years. I was inspired to pull it off the shelf when I saw this article – Native American Heritage | Facebook on the Native American Heritage site. With decades of researching my own family, pulling that old tome off the shelf and seeing McWhorter’s name reminded me of the McWhorters in my own family and once again my family lines became deeper entwined with history.

I spoke of my own awakening to the culture and genocide of Native Americans in The Pursuit of Family Connections. With the discovery of McWhorter’s life, I found a wild, rough, and ready friend in my family’s past, who gave voice to what I had felt as a young boy.

Reviewing Voice of the Old Wolf: Lucullus Virgil McWhorter and the Nez Perce Indians, by Stevens Ross Evans, Montana State University professor Alanna Kathleen Brown wrote,

For over 400 years, while Euroamericans were moving west, they pretended that they settled a “wilderness.” When confronted by native peoples, the vast majority asserted the privileges of a superior race, using force and law to take what they wanted, justifying their greed as the manifestation of divine will. For Native American peoples, their coming meant the largest genocide in human history. McWhorter understood and was appalled. He dedicated his energies to comprehending the cultures of the Native American tribes who surrounded him, and he committed himself to recounting the legends and epic personal stories of those he saw passing. McWhorter also continually argued for fair treatment and decency towards Native Americans whenever he could be an advocate. For this love, he was ridiculed and isolated by many of his own white peers. (3)

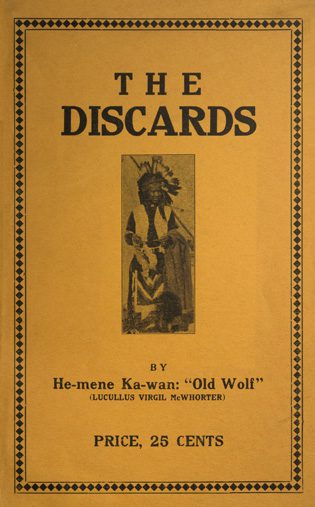

And finally, the most brutal example of McWhorter’s views and advocacy for Indian rights and his work with the Yakima can be found in an obscure tract he produced around 1920 titled, The Discards, By He-mene Ka-wan: “Old Wolf” (Lucullus Virgil McWhorter).

The Discards is available online from The Project Gutenberg and is a fascinating insight to the realities Native Americans faced, expressed not only by McWhorter but by native Yakima Tribe members themselves.

References & Notes:

(1) Guide to the Lucullus Virgil McWhorter Papers 1848-1945, Washington State University Libraries Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections. Ault, N. A., McWhorter, Lucullus Virgil, and State College of Washington. Library. (1959). The papers of Lucullus Virgil McWhorter. Friends of the Library, State College of Washington (ntserver1.wsulibs.wsu.edu/masc/finders/cg55.htm)

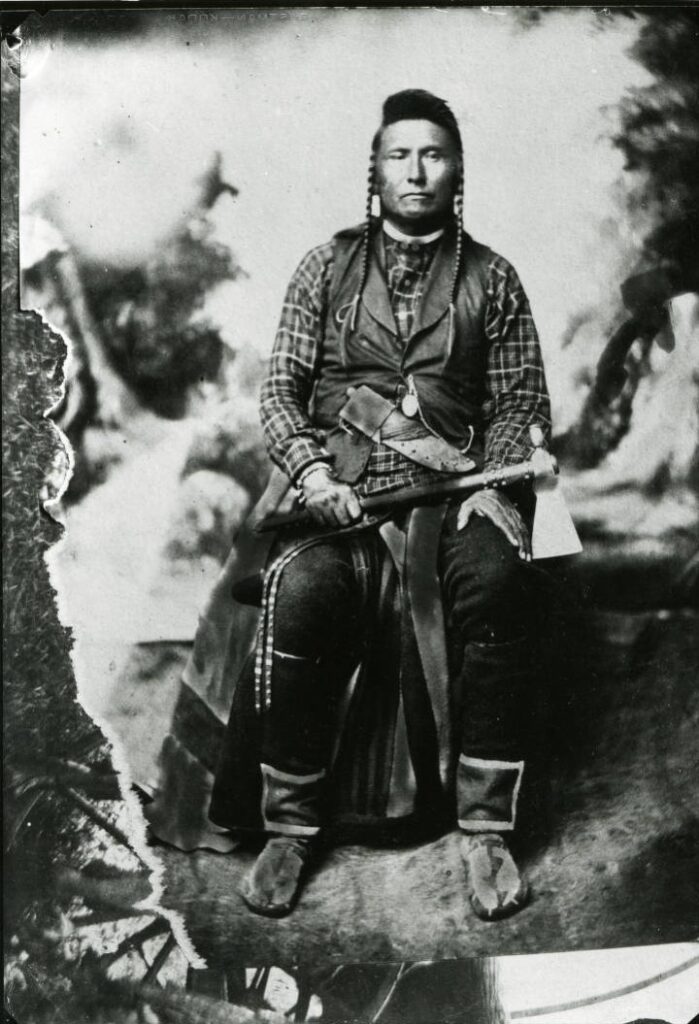

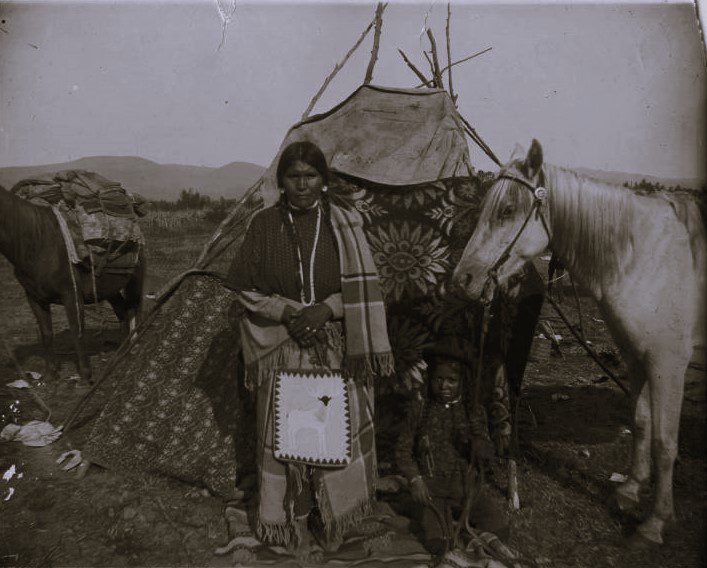

(2) Non-copyrighted Native American Photographs from the collection of Washington State University Libraries Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, McWhorter, L.V. Collection (https://content.libraries.wsu.edu/digital/collections/mcwhorter/search/page/1)

(3) Alanna Kathleen Brown. “Voice of the Old Wolf: Lucullus Virgil McWhorter and the Nez Perce Native Americans”

The following titles are available at the Oregon Trail Genealogy Store. Links at the store take you to Amazon, where you can purchase the titles from your own account:

Yellow Wolf – His Own Story by L.V. McWhorter

Voice of the Old Wolf: Lucullus Virgil McWhorter and the Nez Perce Native Americans by Steven Ross Evans Ph.D., professor at Lewis-Clark State College in Lewiston, Idaho

Hear Me My Chiefs!: Nez Perce Legend and History by L.V. McWhorter

Cogewea, the Half Blood: A Depiction of the Great Montana Cattle Range by Morning Dove