As Ralph Fisk relates in Grandfather’s Story, “On April 10, 1864, a beautiful sunshine morning, he [Nathan Fisk] set out with his wife and nine children to again face the real frontiersman life helping to blaze the trail to a new wild country in Easter Oregon, known only at that time because of the recent gold discovery on Canyon Creek, a small tributary of the upper John Day River.

We had a covered wagon drawn by a four horse team, and a two horse team hitched to a spring wagon, ten head of pack horses loaded mostly with flour, several head of loose horses and about thirty head of cattle, mostly milch cows. Some thirty or thirty-five people with their outfits gathered at Fathers place on Greenhorn Creek to join our train. I do not recall the names of all, but remember that there were D.B. Rinehart, Bart Shelley, Dryed McClintock, J.C. Gillenwater and family, W.B. Davis and family, Mr. Linvel and family, George Barry, John Hallock, Sam Stewart, Eli Irman and a Negro.”

Though Ralph related many stories about their adventure, there had often been a question about the actual path they had taken. The Oregon Trail is not a single trail, but at various places splits off in other ways according to the whims of wagon masters, the pursuit of new locations, and at times misguided directions as emigrants spread throughout the western states.

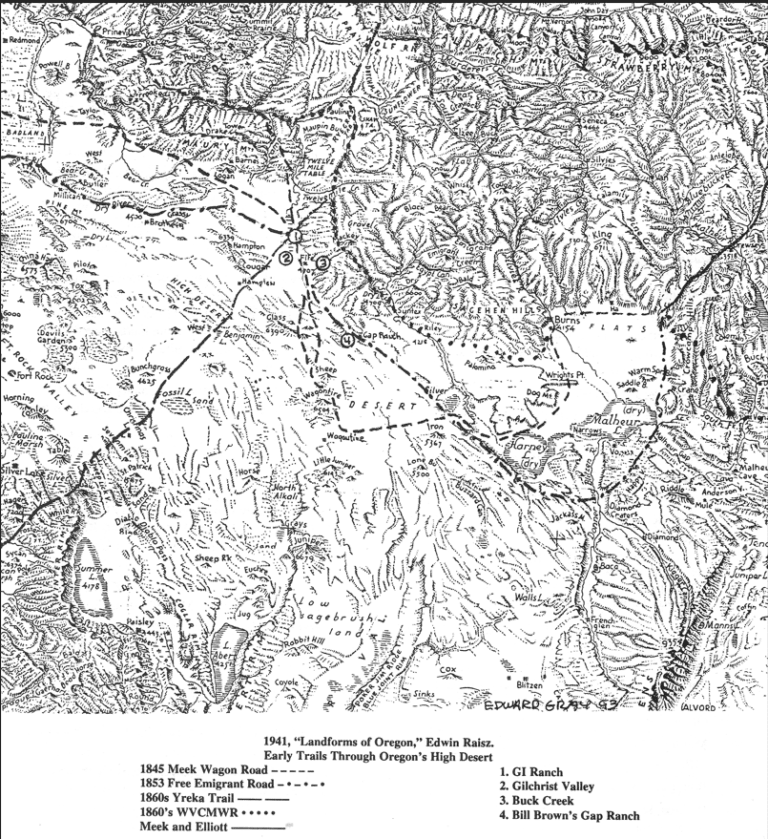

Some of these other trails include the Meek Wagon Road, the Free Emigrant Road, the Willamette Valley Cascade Mountain Wagon Road (WVCMWR), and the Yreka Trail. At times these wagon roads merged or crossed, giving travelers pause to reconsider their destination and perhaps strike out for other greener pastures.

Edward Gray, in his book, William “Bill” W. Brown 1855-1941” doubted that the Fisk Party had used the Yreka Trail in their journey to Canyon City1. But the Yreka Trail entered Lake County, Oregon near Silver Lake, and Ralph is clear about camping by the lake. After some time by the lake, they turned east to face 75 miles of the worst terrain possible, prompted by the fact the Isom Lawrence had traveled that direction three days prior. This trek led them to intersect with the Meek Trail and they “laid over two days at Mountain Springs [Wagontire Mountain] because W.B Davis had broken one of his front wheels several miles back on the desert.”2

There are numerous references that claim the naming of Wagontire Mountain is unknown. Gray also suggested that Nathan Fisk may have been wrong about arriving at Mountain Springs (and implying that the wagon wheel that remained, according to the stories, was not the source of the mountain being named Wagontire). To support this, Gray referenced Captain John Drake’s diary of 1864 which mentioned a Mountain Springs further to the north, back on the Yreka Trail. However, McArthur’s Oregon Geographic Names references the springs on the north face of the mountain at S 31, T 20S, R 24E.3

After a two day layover to repair the wagon (leaving the broken wheel behind), the Fisk party headed north on the Meek Wagon Road, then onto the Meek/Elliot Trail to reach the John Day River, then east to Canyon City. After taking in the city of gold, they passed on, taking the only road out of Canyon City, east up the gulch, out of Marysville, on to Dog Creek close to Prairie Diggins [Prairie City]. As Ralph recalled, “My father, after looking over the country and situations, the new discovery of rich mines having been struck at Dixie up Dixie Creek three miles from where Prairie City now stands, came to the conclusion that farming was just about as good as mining, and as he had to prepare feed for his stock the coming winter, started up the river which at the time was all vacant land – all unsurveyed. A man could take all the land he wanted, so he located enough for three claims on Strawberry Valley opposite Dixie Creek. He was the first settler on Strawberry. My father gave it it’s name, Strawberry Creek, about the last of June 1864. At that time there were just worlds of wild strawberries grew all over the valley and pretty large ones, too, and Prairie chickens by the thousands, some sage hens, a great many wild ducks, coyotes, grey and black wolves in great numbers, fish too many to mention.”4

The mountain was first called Logan Butte by the miners, after the nearby Camp Logan5. With Nathan’s naming of Strawberry Creek, the mountain from which those waters flowed became known as Strawberry Mountain, now part of the Strawberry Wilderness.

Drawn by the lure of gold, Nathan Fisk moved his family to a better life and in doing so fixed prominent geographic names still used today. But in researching the route of the Fisk family from California into Oregon, and documenting how place names came to be, there is still one person, one surprising connection, still left out on the trail.

When Nathan Fisk turned his family east from Silver Lake he did so because Isom Lawrence (as noted by Ralph Fisk) had gone before him three days earlier. This unnamed, unmapped trail linking the Yreka and Meek Trails across brutally dry and rough ground was known by Isom. There was water at Mountain Springs, and Isom, knowing how difficult the trek would be, sent two barrels of water back down the trail to help the Fisk Party. But who was this Isom Lawrence?

1833 1910

Given Ralph Fisk was a boy of 13 years when he set off on the Yreka Trail with his family, and that his recollections were written decades later, it is not surprising that certain memories, and in particular here, spelling of places and names, might not be accurate. So it is with his mention of Isom Lawrence, a name accepted with his story and lost as a mere side event in the Fisk family’s journey to Canyon City.

But in fact, Isom Laurence was Isham John Laurance (1833-1910), who traveled the Oregon Trail in 1857 and first settled in Yreka, Siskiyou Co., California, as had the Fisk’s. In 1864 he took his family north to Canyon City, days before the Fisk family embarked on the same journey. Once in the John Day Valley, the connections between the Laurance’s and Fisk families deepened. Isham’s son John (1862-1944), a mere toddler on the trail to Oregon, grew up in Prairie City, eventually marrying Anne Elizabeth Deardorff (1870-1962), and their son Frederick married the granddaughter of Ralph Fisk, whose stories began the entire history within this article.

Footnotes:

- Gray, Edward, William “Bill” W. Brown 1865-1941: Legend of Oregon’s High Desert. 1993. Your Town Press, Salem, Oregon. Pg. 17.

- History of Grant County. 1983. Dallas, Texas. Pg. 64

- McArthur, Lewis A., Oregon Geographic Names. 6th Edition, 1992, Oregon Historical Society, Portland, Oregon. Pg. 873

- Fisk, Ralph, “Ralph Fisk Relates Some Pioneer History – Came to Canyon With Father in 1864.” March 17th,1922, Blue Mt. Eagle Newspaper.

- McArthur, Lewis A., Oregon Geographic Names. 6th Edition, 1992, Oregon Historical Society, Portland, Oregon. Pg. 802

- Header Map – Reproduced from Footnote #1. Map image signed by Edward Gray, indicating his hand drawn locations of trails on Edward Raisz’s 1941 “Landforms of Oregon”

Terri Thompson

Mark, I will use “they settled in Ashland, Jackson County in 1852” for your Certificate. I had no doubt he was a Pioneer, just wondering what date and place to put in our records. Your documentation of your family history is outstanding! I will be sharing your web page with our President tomorrow. I have found it to be very informative! If I finish everything tonight, I will have our President sign the Certificate tomorrow and get it mailed to you soon thereafter.

Terri