The interview above took place in 1989 and contains Howard’s memories related to working for the Oregon State Police’s Game Commission, and of course, his extensive knowledge of Northeastern Oregon’s wildlife and fish habitats. Conducted by Jerry Gildemeister, it is a priceless view of Oregon wildlife, when the wildlife was wild…

There was a time in the Oregon Territory when the animal populations had an ebb and flow of their own natural design. All of us who have studied the Oregon Trail, and the lives of the early settlers out west, can recall countless references to the prairie dog towns, the antelope, buffalo, snakes, prairie chickens, and deer. Other species like beaver, river otter, martens, and fox brought trappers deep into the unmapped west. Our ancestors likewise encountered this abundance of wildlife, and many are the stories of bear, cougar, coyote, moose, badger, lynx, and elk.

And these animals fed our people. There were no limits on what could be killed or how many. Our ancestors took what they needed to survive. Not until the late 1800’s did the first conservation laws come in to play, first to protect streams and fisheries, then later there would come limits on deer, elk and other big game. The Oregon Dept. of Fish and Wildlife has a historical timeline of these changes in our relationship with wildlife. But that is really not what this story is about.

The story I actually have to tell was written 40+ years ago…

“I used to go bow hunting with my father and my great Uncle Howard in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. Uncle Howard would always take us to where other hunters wouldn’t go (though in later years they found us, as their numbers grew). I had the sense of avoiding the weekend hunters and going to where I felt Nature was deeper and more private. It was here that lessons could really be learned, lessons that only the deep forests would reveal. When it came to these forests Howard was, and still is, my hero. I thought he knew everything about the outdoors, the animals, the plants, and how to survive. He could move through the forests like a man walking through his home after dark, knowing where everything was, never smacking his shin on the coffee table. I was full of wonder while in the forests and Howard could answer all my questions about bugs-dirt-why-birds-how-stars-sunsets.

One late night we bounced along in his old Willys jeep at the end of a successful hunt (we didn’t get anything), in silence, just staring ahead as the jeep lights pushed a swath of darkness aside. Howard had already taught me that there was as much to see in the dark as there was in the light, so I never let fatigue keep me from the intent, expectant stare into the swath of light ahead. Suddenly the silence was broken as Howard exclaimed, “Did you see it?!” And when we asked, “What?”, he said that it was gone, and we all fell silent again. A couple more miles of our lights bouncing through the darkness went by when he said, “There!”, and of course Dad and I once again saw nothing.

He then told us about something so beautiful that I have spent all my life looking for it. I have never seen it, yet I instinctively always look. He told us that sometimes, as you stare into the headlights, a moth will be there, positioned just so, and the light will reflect for an instant upon its tiny compound eyes. He made it sound like when that happened you would see the most wonderful light reflected to you. He made it sound like it was the most beautiful light in the world, rare, elusive, and so very special.

Oh, how I wanted to see that light! As the years have gone by, I imagine that light, more wondrous than diamonds on water, or a rainbow, or the emerald, green flash at the end of a perfect sunset over the ocean. It was the ultimate flash of light in Nature, its brilliance unheralded. And so, the years have gone by, and I’ve searched the eyes of a thousand moths in my headlights. In a moment of my youth, I believed the story about the moth, and that incredible light that filled him with such wonder on that dark night long ago. Howard was a great storyteller, filling time with tales, while giving me something to believe in, something I may never see, yet so real.

A few years went by, and I was still thinking about this moth flash. I began to have doubts. Howard opened the natural world to me. I have studied it, lived in it, intertwining Nature throughout my life. As I grew up and learned more about Nature, Howard’s stories would come back to me and I’d say to myself, “Yep, that’s true”, “Yea, Howard taught me that”, so that through those years all his stories were real except one. Was the light reflected from the eyes of a moth just another story born of that twinkle he often had in his eyes? Hence, the doubt. I became disappointed when I began to believe it was a story, rather than believing in the light.

I went to see Howard and Melba on their 50th wedding anniversary. When I got the chance, I raised my doubts about the light to Howard and his reaction was if I had punched him in the gut. How could I not believe in the light, and “was it true I hadn’t seen it yet”, and “good God” I couldn’t stop looking! After the shock left his eyes, it was replaced by a light, the twinkle of his storytelling. Aside from the guilt of disbelieving, I was once again filled with the wonder of that light, at the possibility of one day seeing that light. I think the light I’d been looking for was in his eyes that day. Howard taught me a great many things about the wonders of Nature, but the greatest thing he taught was to look into the eyes, and let your sense of wonder keep you searching, for the wisdom comes in the search, not the answer.

The next time you’re driving at night, watch for the light reflected from the tiny compound eyes of a moth. There is no more beautiful light than that.”

In the hard life of settling a new territory and subsisting on the land, there evolved in our ancestors a parallel intimacy with Nature, an understanding of seasons and cycles and interactions that rose above the quest for survival. For to survive, this understanding of nature, like Howard had, was critical, and bred the first whispers of conservation.

Men like John Burroughs (1837-1921) wrote essays about the state of our natural world and conservation but, like Howard and others, he was also an ardent hunter and fisherman. This deep understanding of wildlife bred respect for the natural world. I love the lead photo in this article of Howard kneeling next to a fawn, for I see the man that taught me to love the wild in the wilderness. I see a man who hunted and fished with such passion that he came to embody a deep understanding of the natural world, and then, in his own way, strove to save it. The Save The Minam River campaign and The Eagle Cap Wilderness are but two fruits of his labor.

Which brings me back to the recorded interview I’ve included. The interview is long I’ll admit, but it is also a rare glimpse into a man who deeply understood the natural world through a lifetime of observation, and yes, hunting and fishing, which reveal the intricate connections, the ebb and flow, of the natural world. Howard also reminds me of those distant connections with our ancestors who settled these western lands, and how their lives 150 years ago irrevocably shaped the lives that we have now.

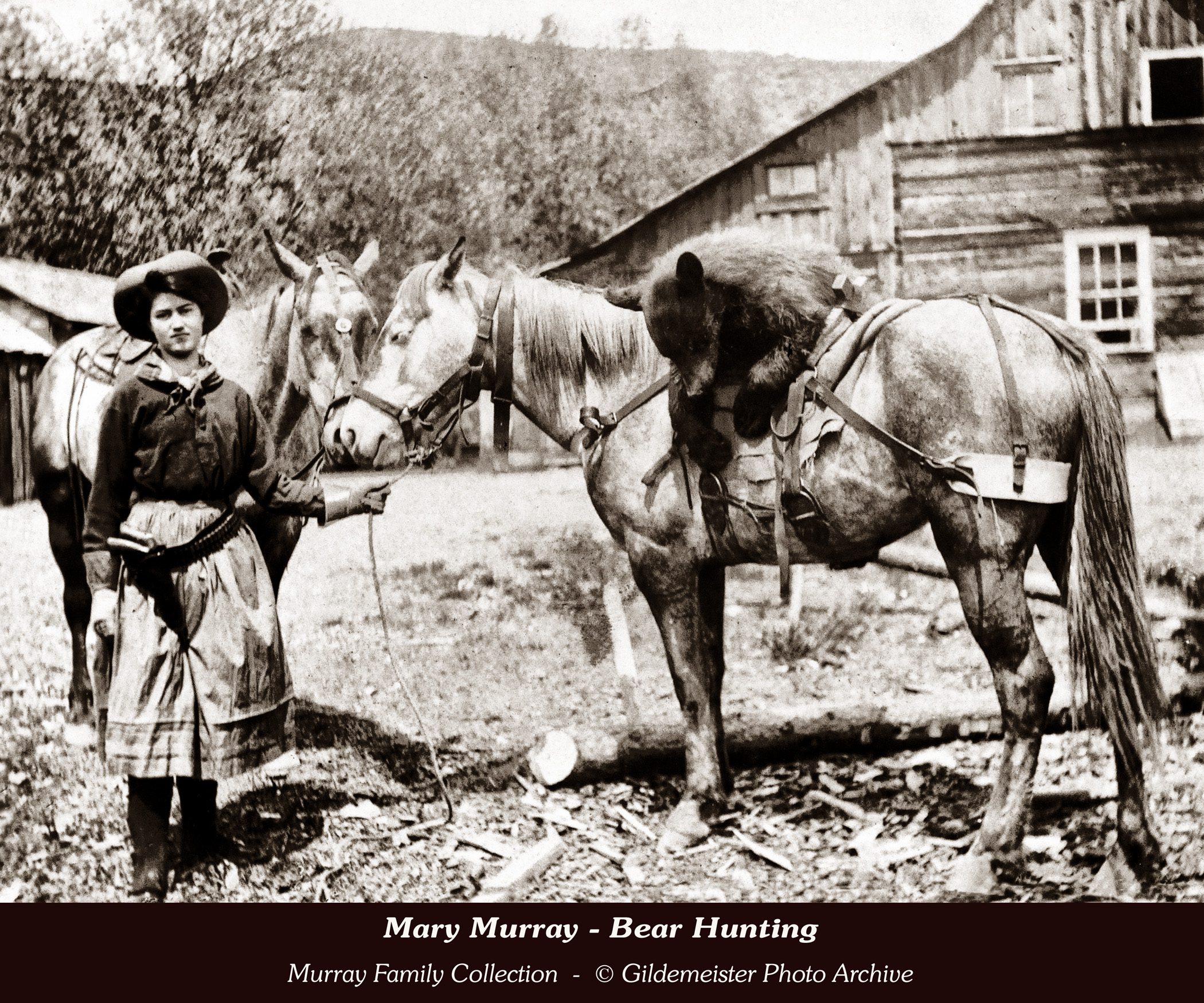

Jerry Gildemeister collected oral histories from 39 people across eastern and northwestern Oregon nearly 40 years ago, the youngest age 47, the oldest storyteller aged 90. We have lost most of those voices now, as I have lost my beloved great Uncle Howard. Excerpts from Howard’s recorded interview above, and history related by the others, were published by Gildemeister’s Bear Wallow Publishing Company in a book titled, “Bull Trout, Walking Grouse and Buffalo Bones – Oral Histories of Northeast Oregon Fish and Wildlife” from a 1992 Report (see overview below), Reprinted in 2019 by Jerry Gildemeister for the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife. Out of print since then, is once again available through the shop at Oregon Trail Genealogy in an effort to keep these valuable oral histories alive. Order a copy now!

Click to purchase Bull Trout, Walking Grouse and Buffalo Bones

View the full collection of Union County Oral History online, courtesy of the Pierce Library, Eastern Oregon University